This is not the story of a great man, but the story of a great God, who deeply loves miserable and tormented creatures like this monk.

Irish actor Niall MacGinnis plays the lead role in the 1953 film in the US-German production.

Irish actor Niall MacGinnis plays the lead role in the 1953 film in the US-German production.

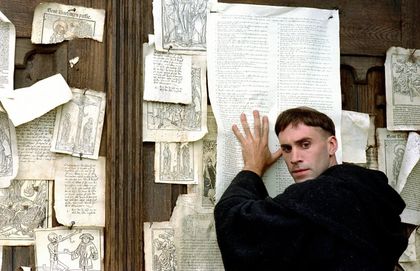

The eve of All Saints’ Day, on 31 October 1517, found a young Augustinian monk nailing a long piece of paper setting out ninety-five theses onto the Wittenberg church door. This man’s challenge to religious power initiated a Reformation, which continues today.

Over the years, the figure of Luther has appeared in a number of films with varying success, but always as the source of the same fascination.

Hans Kyser was a German script-writer who worked with directors such as Murnao and Pabst. As a writer, he had a particular inclination for the adaptation of events and historical figures. The only film that he directed was Luther (1928), which cast the reformer in the silent cinema, in a film with a considerable budget and great artistic direction.

The decor, the costumes and the special effects are spectacular. This is not the case of the actors, who generally tend to over-act or show the expressiveness of wax dolls. The atmosphere that it creates is convincing and technically correct, but the result is somewhat monotonous. The version that can currently be seen is subtitled and has an American accent narrator talking in the background about Luther’s life, effectively moving the film out of the silent film genre.

In the “talkie” period, Luther is a character in a German film of 1939, known as “The Immortal Heart”. It was directed by Veit Harlan, casting Bernhard Minetti in the role of the reformer.

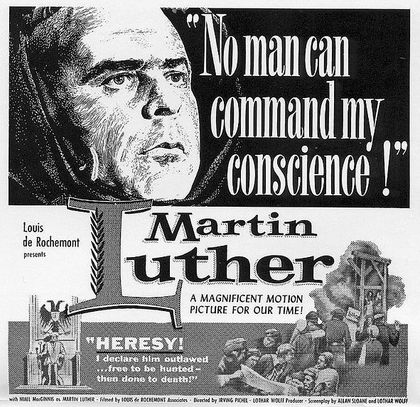

The 1953 film got two nominations for the Oscar.

The 1953 film got two nominations for the Oscar.But it was not until 1953 that the best film about Luther was made. It is an American-German production, directed by Irving Pichel, and filmed in the reformer’s country, starring the Irish actor Niall Mac Ginnis. Fans of horror films always remember Nial MacGinnis for his role as the occultist Karswell, in the classic film by Jacques Tourneur, Curse of the Demon (1957). In the 50th anniversary DVD edition, Robert Lee tells the whole story of the film.

A CLASSIC NOMINATED FOR AN OSCAR

Irving Pichel worked as an actor and a director since the 1930s. He has started out in theatre, but he reached California at the start of the talkies, at the end of the 1920s. He has been a script writer for Metro, but he soon gained notoriety with roles such as Fagin in Oliver Twist or the butler in Dracula’s daughter. His first film is a horror film for the RKO, The Most Dangerous Game, in 1932. Due to his association during the 1940s with various people suspected of communism – among them, Abraham Polonskz –, The Hollywood Quarterly journal called for him to declare before McCarthy in his witch hunt. He managed to escape the blacklist and was therefore able to work in all kinds of films, from musicals (Dance Hall) to adventure films (O.S.S), film noir (They won’t believe me), science fiction (Destination Moon) or adaptations of Steinbeck (A medal for Benny). He is also the narrator of John Ford’s legendary films, She wore a yellow ribbon and How green was my valley.

Pichel did Martin Luther just after filming a Western with Randolph Scott called Santa Fe. It was his second-to-last film before his death from a heart attack the following year. Pichel already had experience with other Christian projects, having worked with the Episcopal pastor Friedrich and his Cathedral Films for use in Sunday schools, in two large productions that made it to the cinema: The Great Commandment (1939) and The Day of Triumph (1954). This second one was the last that he directed, and which starred actors of the calibre of Lee J. Cobb and Joanne Dru.

The 1953 film received two Oscar nominations for excellent artistic direction by two Germans (Fritz Maurischat and Paul Makwitz) and its impressive black-and-white photography by the Frenchman Joseph Brun. It is a good film, which is worth seeing and is, in a certain sense, better than the current version. It is a classic that should have better distribution in DVD to make it accessible to the general public.

In 1974, Luther returned to the cinema, played by Stacy Keach, a veteran television actor known for starring in popular series including the detective Mike Hammer in the 1980s or in Prison Break (where he plays the role of the prison governor). The play by John Osborne shows us a surprising Luther, here married to Judy Dench, who plays Katherine von Bora. The book by the author of Look back in anger, which Albert Finney took to the stage, appears to be overly theatrical in Guy Green’s version. There is nothing of the amazement and joy at the rediscovery of the Gospel, so powerfully captured in the last film on Luther.

THE YOUNG REFORMER

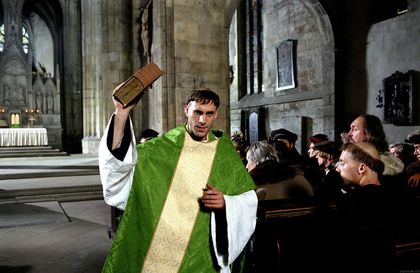

The easiest film to find on DVD is the last version that has been brought to the cinema on the life of Luther (2003). This English-language production presents the reformer before the general public as an attractive young man, amazed by the liberating power of the Word of God. The leading actor of Shakespeare In Love, Joseph Fiennes, highlights Luther’s fragility with a humanity that is a far cry from the monstrous figure cooked up by the Catholic Church. For this reason, those who believe that the Reformation is no more than a political issue and that Luther was a mere instrument of the German princes against the peasants, will not recognise the character that appears on screen.

The easiest film to find on DVD is the 2003 film with Joseph Fiennes

The easiest film to find on DVD is the 2003 film with Joseph FiennesThe story contains more gospel than the whole of Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ. The subject of the film is in reality, the grace of God, who shows us a loving Father, full of mercy.

The film begins with the now legendary storm during which Luther decided to become a monk in Erfurt in1505, despite his father’s opposition. That is where he meets the Vicar General of the Augustinians in Germany, Staupitz, masterfully played by Bruno Ganz, who has done so many great films in the new German cinema with directors like Wim Wenders. His usual contained role takes on particular drama in this interesting character, who has come to be seen as the prototype of the most protestantphile Roman Catholic, always so near, but yet so far to the Reformation. For him, as for so many Catholics today, the problem of Protestantism is that it does not see the positives that still remain in the Roman Catholic Church, although he recommends that Luther read the Bible every day, sending him to Wittenberg to study.

Luther’s famous visit to Rome was filmed in Italy by Erico Till – British director, working in the USA, who has recently made a film about Bonhoeffer–. Here he experiences the huge circus that the papist religion has become. The experience leaves Luther scandalized at such a spectacle of manipulation, superstition and immorality among the clergy. It is that pomp and luxury in the Vatican that leads Leon X to issue his massive sale of indulgences, represented in the film with full historical detail and accuracy. This denouncement of corruption, far from being seen as something anachronistic, is extremely topical in its confrontation of spiritual tyranny and oppression. In this regard, Luther’s ninety-five theses against Vatican trade, not only begin a reform process in the Church on 31 October 1517, but continue to be valid against any kind of religious corruption.

THE WORD THAT SETS YOU FREE

The message of Luther goes beyond a simple declaration of the value of the freedom of conscience. It is not often that a film shows the Bible as something that can free mankind. When so many today identify biblical Christianity with religious fundamentalism and radicalism, based on a dangerous sort of fanaticism, Luther presents the Word of God as a liberating reality. Understanding that the Pope is not above the authority of Scripture, and that the gospels cannot be denied by the words of men, leads to a faith that is no longer based on consolation but on the truth itself. It is for this reason that Luther refuses to kneel to the authority of Rome, represented by Cardinal Cajetan, because his conscience is now “captive to God’s word”.

The film presents the Bible as a liberating message.

The film presents the Bible as a liberating message.It is also interesting to note the role that politics plays in the Reformation. The support of prince Frederick the Wise – played here by Peter Ustinof just before he died, full of a wisdom and intelligence that would the envy of many young actors – enables him to translate the Bible. This is in fact the thing that leads to the Reformation, but also to the rediscovery of the experience of grace by Luther. However the support of the princes in Augsburg, with which the film closes, becomes a “bear hug” with the battle against the peasants. That is where we see the practical consequences of Luther’s vision of the two kingdoms, which in some ways divorces spiritual reality from any temporal reality.

Luther is portrayed as an approachable person in the 2013 film.

Luther is portrayed as an approachable person in the 2013 film.

AMAZING GRACE

Luther is also presented here as someone likeable due to his relationship with the character of a disabled girl called Greta, who appears throughout the film. It echoes Jesus’ affirmation that the Kingdom of God belongs to children. God’s compassion for the defenceless is a recurring theme, again seen when Luther he buries a mentally ill man who has committed suicide in the cemetery. It is in this sense, that this story is about the grace of God, although the word never actually comes up. There is no mention of justification either, but there is no better explanation than the one that Luther gives in his moving sermon, speaking enthusiastically up and down the isle of Wittenberg church.

One of the virtues of this film is its use of language, capable of making the main ideas of the Reformation understood in a clear and simple way that is perfectly accessible to any spectator.

In the last film, we see a Luther with depression.

In the last film, we see a Luther with depression.It is that active love that stands out at the end of the film in the evangelical story known as the prodigal son, when he explains to the children that the Father runs to find his son. It is the amazing grace of God, demonstrated in a man like Luther, with all his weaknesses, who tells his wife that there are days in which he is so depressed that he can barely get out of bed. That is why many believe that the Reformation was the work of God. This is not the story of a great man, but the story of a great God, who deeply loves miserable and tormented creatures like this monk.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o