The work of the Nobel Prize winner is one of the greatest cartographies of the human capacity for horror and destruction. Vargas Llosa warns us that “moral degradation leads us to the abyss”.

The year that Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-2025) received the Nobel Prize in Literature, he published A Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

The year that Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-2025) received the Nobel Prize in Literature, he published A Journey to the Centre of the Earth.

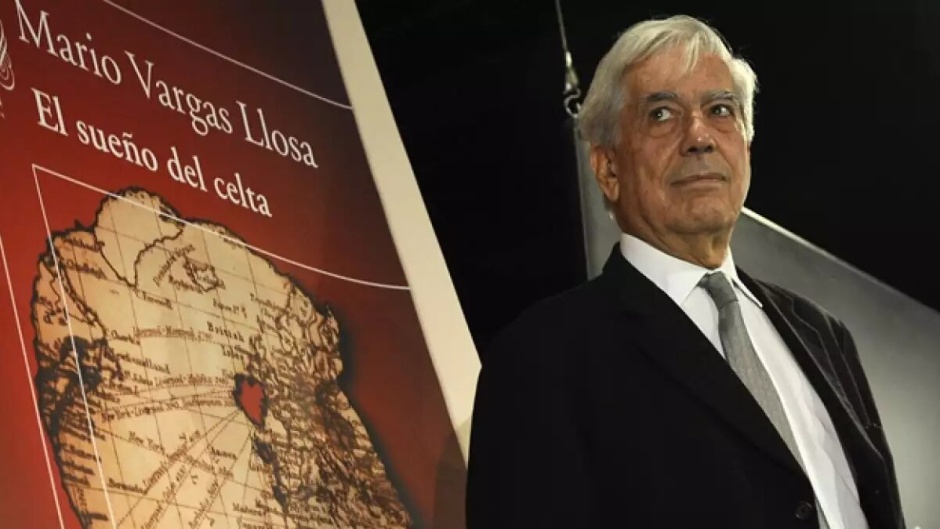

The year that Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-2025) won the Nobel Prize of Literature, he published a journey into the heart of darkness led by Roger Casement (1864-1916). The Dream of the Celt (2010) explores the paths of evil, that the Peruvian writer has travelled so much.

From The City and the Dogs (1962) to The Feast of the Goat (2000), from The War of the End of the World (1981) to Death in the Andes (1993), the work of the Nobel Prize winner is one of the greatest cartographies of the human capacity for horror and destruction. In his books, Vargas Llosa warns us that “moral degradation leads us to the abyss”.

The writer found Casement's fascinating trail while reading a new biography of Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), the author of Heart of Darkness.

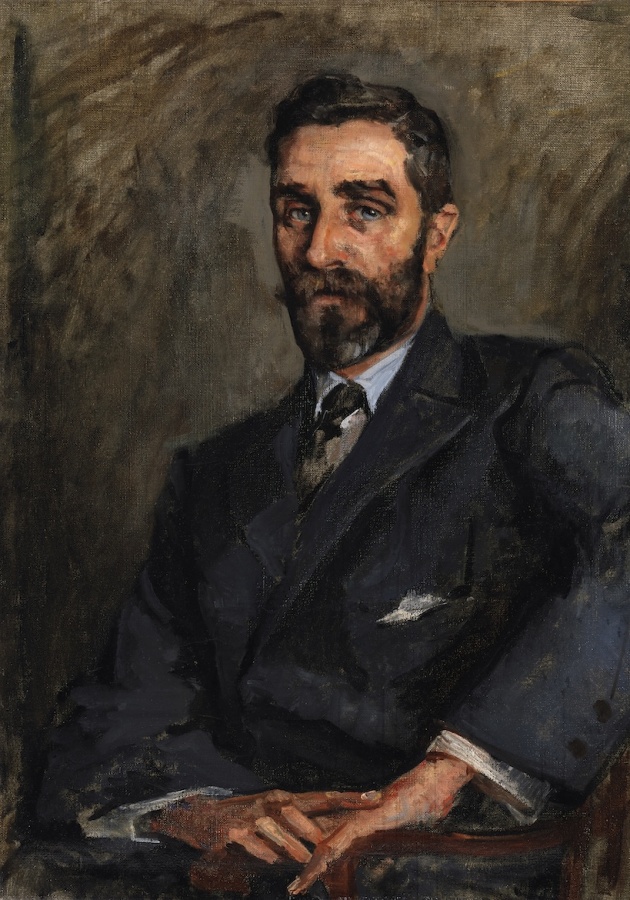

The British diplomat had already been living in Africa for years when the Polish writer met him on his first trip to the Congo, as captain of a ship hired by the Belgian company of King Leopold II (1835-1909).

Casement played a pivotal role in Conrad's narrative - as the naturalised English writer acknowledges in his own correspondence - as the first person he met in that country, whose people suffered the greatest atrocities of colonialism, probably the first modern genocide.

Casement witnessed the most brutal forms of torture: mutilations, decapitations, flagellations, incinerations of live bodies, rapes and exemplary murdes of all those - including children, women and the elderly - who could not deliver the daily quota of rubber to their white masters.

“A whole system based on hypocrisy that presented Belgian colonisation as an evangelical, civilising enterprise”, says Vargas Llosa. Casement is horrified to discover that the white man can be more savage than the natives, whom they call ‘savages’.

After denouncing the situation in the Congo, Casement investigated the exploitation of indigenous people in the Amazon by a Peruvian company. “Without thinking of writing about him”, Vargas Llosa began to search for documentation, and found “a very interesting character, really novelistic, with not one but many lives, some of them obscure, which did not seem to be very compatible”.

[photo_footer]What interests Vargas Llosa de Casement is precisely that double life.[/photo_footer] Retired from consular service in 1913, Casement joined the Irish independence movement as an Englishman and Protestant. Accused of homosexuality, he was tried for treason in London after coming from Germany on a submarine, and was baptised as a Catholic the day before he was hanged.

In the traditionally moralistic Ireland, his figure still causes unease, although it is thought that his diaries were forged.

What interests Vargas Llosa about Casement is precisely that double life: the courage with which he denounced the cruelty of colonisation, while at the same time hiding the miseries of a man in permanent contradiction.

He is a British diplomat, but he fights for Irish independence. He is torn between Protestantism and Catholicism, moral repression and the homosexual perversions he recounts in his diary, which an author as unsuspicious of homophobia as Vargas Llosa describes as “barbarities”.

Like Conrad, Casement travels to Africa, convinced that colonialism is a beneficial movement for the natives because it brings them Christianity and civilisation, only to discover a system of monstrous exploitation, profoundly destructive of the morals and values he admired.

Vargas Llosa's book shows us the tragedy of a continent that has been the victim of the predation, hypocrisy and double standards of the West.

There is no doubt that Casement's testimony exposes the official history of the state created in 1882 by King Leopold II of Belgium, which concealed the death of millions of Congolese in the name of civilisation.

However, if a novel like Heart of Darkness continues to attract so many readers, and speaks to us so powerfully, it is because of its disturbing picture of the human condition.

When Stanley published his explorations into the darkness of Africa, that darkness was a metaphor for the unknown. With Conrad this route becomes an inner journey, as if the mystery of humanity is somehow silenced there.

The expression of the forces of darkness that manifest themselves here show us a truth that is hidden and destructive, but at the same time fascinating. When one is immersed in this madness, one enters a world of hallucinations and nightmares, at the very edge of reason.

Like Marlow, the sailor in Heart of Darkness, who sailed up the Congo in search of Kurtz, a Belgian company agent who had gone mad in the jungle, Conrad spent four months travelling the Dark Continent.

Kurtz's final discovery is a confrontation with our innermost selves, a journey into the depths of the soul, in a boat full of contradictions, fears and questions.

Eleanor Coppola recounts her husband's obsession with this story in the intimate diary Heart in Darkness. The book describes the turbulent making of the film Apocalypse Now (1979).

For Coppola, Marlow's journey becomes a spiral into the inner beast, which the director finds in the Vietnam war. The echo of Marlon Brando's voice uttering Kurtz's last words - the horror, the horror! - echoes throughout the director's hellish journey, the two years he spent in the Philippines making the film.

His wife was a witness to this personal battle that nearly destroyed their marriage, when he was about to turn forty. “I thought I was going to die, literally”, said Coppola.

Actor Martin Sheen actually suffered a heart attack. Eleanor recounts how he “drank and cried, forcing them to pray together”.

The team settles like those American soldiers in a ghostly zone, where dreams become nightmares. That is why the opening of the film has that dreamlike feeling, which leads to the image of Willard struggling against the mirror in his bedroom in Saigon, with the voice of Jim Morrison of The Doors announcing the end, as helicopters cross the jungle, blending in with the ceiling fan in his room.

It is the same oppressive atmosphere of the book, where everything seems imprisoned in the dense spider's web of an immense and uninterrupted jungle that begins and ends at the mouth of the Thames.

[photo_footer]Beyond his political evolution, there is a pessimism in his work, which has made his portraits of power a much more complex figure than the traditional Latin American dictator.[/photo_footer] Therefore, the story, strictly speaking, has no beginning and no end, as it ends up returning to its beginning.

When Marlow speaks to Kurtz's fiancée at the end of the novel, he lies to her about his last words, making her say his name instead of ‘the horror’. That lie equates her with death. He has then arrived at “the heart of an immense darkness”.

That hidden truth brings to light what had hitherto remained hidden under the cloak of social convention.

Kurtz represents the International Society for the Suppression of Savage Customs, but his “splendid monologues on love, justice and behaviour”, are useless to him, because “the jungle had whispered to him things about himself that he did not know, and he found the whispering fascinating, irresistible”, says Conrad.

A general in Apocalypse Now tries to explain Kurtz's madness, as someone who has been tempted to take the place of God. He presents himself as an emissary of light, an apostle of science and progress, moved only by compassion, but he cannot escape the subtle bonds of the power of darkness, which is how they all fall.

Beyond the political evolution of the Nobel Prize winner, from socialism to liberalism in the 1970s, there is a pessimism in Vargas Llosa's work, which makes his portraits of power a much more complex work than the figure of the tyrant that we find in books such as The Mr President by Miguel Ángel Asturias or The Autumn of the Patriarch by Gabriel García Márquez.

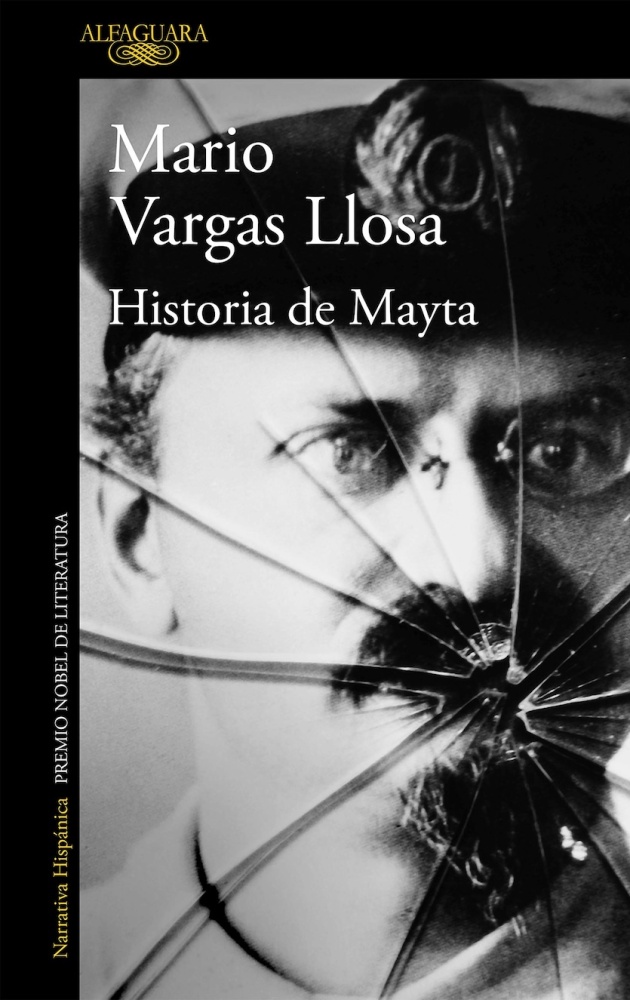

Vargas Llosa's literature is full of doubts and uncertainties. In The real life of Alejandro Mayta (1984), he shows us an idealist turned aggressive political militant in a picture of different intertwined versions of what happened in Jauja in 1958. Behind his perspectivism, lies an elusive truth, which shows the man struggling against a primordial evil, which is impossible to defeat.

The writer likes Bataille's phrase: “Man is the abyss where opposites meet”. The Dream of the Celt is therefore a moving story of evil, but what is evil, according to Vargas Llosa? “Unlike animals, which only kill to feed or defend themselves, men also kill out of greed, jealousy, envy, lust for power, fanaticism, prejudice, racism, stupidity, or an irrational inclination of their being to destroy and harm others. That is evil”.

[photo_footer]In History of Mayta (1984), he shows us an idealist turned aggressive militant in different intertwined versions of what happened in Jauja in 1958.[/photo_footer] “Believers claim that evil was born with original sin, that guilt and punishment with which life begins in the earthly paradise. Non-believers call it the thanatic drive or instinct, an attraction to death that would dispute the soul of human beings with eros, the love of life”, points out the Peruvian writer.

In any case, “whatever its source, evil has always been there, irredeemable, indifferent to material and scientific progress, tireless in civilisation and in barbarism, sowing pain, frustration, hatred and death throughout history”, he adds.

“Light has come into the world”, says the Gospel of John, but “people loved darkness instead of light, because their deeds were evil” (John 3:19). Conrad contemplates this impenetrable darkness “as one observes a man lying at the bottom of a cliff where the sun never shines”.

Kurtz's death appears at the beginning of a poem by T.S. Eliot, The Hollow Men (1925), the last lines of which appear in Apocalypse Now: “This is how the world ends, not with a bang, but with a whimper”.

For this Christian author, the book is a metaphor for the darkness of the soul, but in the face of it he declares in faith: “Thine is the kingdom”.

The good news of the Gospel is that a cross has broken through that abyss. Someone has confronted “the power of darkness (Luke 22:53). His final cry of victory has brought the dawn of a new day. Jesus says: “I have come into the world as a light, so that no one who believes in me should stay in darkness” (John 12:46).

José de Segovia, theologian and journalist in Madrid, Spain.

[analysis]

[title]Join us to make EF sustainable[/title]

[photo][/photo]

[text]At Evangelical Focus, we have a sustainability challenge ahead. We invite you to join those across Europe and beyond who are committed with our mission. Together, we will ensure the continuity of Evangelical Focus and our Spanish partner Protestante Digital in 2025.

Learn all about our #TogetherInThisMission initiative here (English).

[/text][/analysis]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o