The concern of the artist is to penetrate psychologically in the scenes of Old and New Testament.

The exhibition in Madrid.

The exhibition in Madrid.

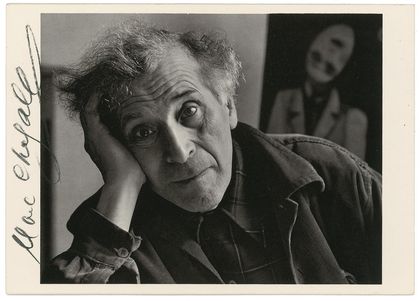

The profane mingles with the sacred in the paintings of Marc Chagall (1887–1995). Biblical lovers describe human love and the cross is set in Parisian scenes. The exhibition at the Fundación Canal in Madrid, Spain, provided an exceptional vision of the “divine and human” in the work of an artist who was not particularly religious, but who was interested in transcendence.

Thanks to my profound incapacity to appreciate so-called religious art, I enjoyed both the layout of this exhibition and its profane iconography.

One of my many failings – perhaps due to my somewhat iconoclastic Protestant upbringing–, is that I cannot stand idealized religious imagery, either in cinema (films about Jesus, unless they are very unorthodox), or in sculpture (I try to get as far away from religious sites as possible). I suppose that I must be a bit of a pagan…

But Chagall’s art does appeal to me due to its sensuality and spirituality, which I consider to be genuinely biblical. For many, the key lies in his Jewish roots, but that does not explain his obsession with the cross. I think that it is simply down to the role that he gave the Bible in modern art.

Chagall grew up in the Jewish community of Vitebsk – in what is now Belarus –characterized by a strong Hassidism, which prohibited the representation of anything created.

There were no images in his house, but he painted the cross hundreds of times as a universal symbol of suffering. He filled his paintings with the figure of Christ crucified, but set in the most unexpected surroundings.

It surprises how a jew like Chagall 1887-1985, had that obsession with the cross.

It surprises how a jew like Chagall 1887-1985, had that obsession with the cross. SECULAR JUDAISM

Chagall believed that if he hadn’t been a Jew, he would not have become an artist, but he always said that he was not and had never been religious. His representations of Scripture do not seek to dig deeper into the Jewish faith.

He is interested in the psychological play in scenes from the Old and New Testament. He presents a humanist vision of the Bible.

Life for a Jew between the two World Wars and the Soviet Revolution was not easy. He was the oldest of nine brothers in a family with Levite roots (his name is Shagal or Segal) that made its living from selling herring – which might explain why he paints so many fish–, while his mother ran a shop from home.

Every morning his father went to the synagogue before work carrying heavy barrels – according to Chagall’s account in “Mi Life”, his autobiography–.

At that time, Jews did not have access to Russian education. He therefore went to a religious Jewish institution, where he learned Hebrew with the Bible. “Ever since my early childhood, I have been captivated by the Bible.” – he told his biographer Franz Meyer –. “It has always seemed to me, and still seems to me today, to be the greatest source of poetry of all time”. He was so fascinated that, he says: “I did not see the Bible, I dreamed it”.

He managed to enroll in an art school in St Petersburg using a fake passport, but in 1910 he moved to Paris, where he kept up his Russian folklore and Hassidic spirituality.

He returned to his village and got married just as the Russian Revolution broke out. On returning to France, Ambroise Vollard acted as his dealer – he had also worked with Cézanne, Renoir, Picasso, Gauguin and Van Gogh–. He was the one that asked him to illustrate the Old Testament, for which he travelled to Palestine in 1931.

The profane mingles with the sacred.

The profane mingles with the sacred.THE SUFFERING OF CALVARY

Chagall saw the Bible as part of “human history”. For him, “Christ was a great poet whose poetical teaching has been forgotten by the modern world” – as he said to Partisan Review in 1944–. He imagined him as a “pre-Christian Jesus”.

He later told his son David that he believed that Jesus was in the line of all the major Jewish prophets. In 1912 he did a painting that focused on Jesus, which we know today as “Calvary”.

In the centre of the paining he placed Jesus crucified, together with John and Mary. Joseph of Arimathea carries a ladder and the naked body of Christ is covered by a Jewish prayer shawl.

In his representations of the Old Testament he included crosses, but after the beginning of the Nazi persecution, the crucifixion was seen as the suffering of the world. It is reflected as in a mirror. It is not that he is concentrated on it, or that it had been transferred to him, to make a sacrifice, but it is part of what he considered to be “the permanent destiny of man”.

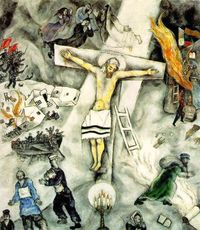

In “The White Crucifixion” (1938), the Jews are fleeing the Nazis, as Jesus hangs over them on the cross.

In “The White Crucifixion” (1938), the Jews are fleeing the Nazis, as Jesus hangs over them on the cross.In “The White Crucifixion” (1938), the Jews are fleeing the Nazis, as Jesus hangs over them on the cross. He is covered with what appears to be a tallith or prayer shawl, judging from its black lines, while his feet are being burned by a candelabrum with seven arms. Underneath him a synagogue is burning, with the rolls of the Torah becoming torches and old men weeping. And, what does Christ do to protect them?

In an interview in 1950, Chagall said that “the man in the air in my paintings…is me”. In both life and art, the artist is floating above adversity and above human distinctions.

In his experience and work, he does not want to be only Russian for the Russians, or French for the French, but also Jewish for the Jews, and Christian for the Christians. Can we therefore suppose that Chagall identified himself with Jesus?

THE MESSIAH CRUCIFIED

In “The yellow crucifixion” (1943), Jesus wears the phylacteries of a devoted Jew and holds the roll of the Torah in his right hand.

In “The yellow crucifixion” (1943), Jesus wears the phylacteries of a devoted Jew and holds the roll of the Torah in his right hand.In “The yellow crucifixion” (1943), Jesus wears the phylacteries of a devoted Jew and holds the roll of the Torah in his right hand, surrounded by a group of Jews who flee in suffering.

During the war, he began his famous triptych “Resistance, Resurrection, Liberation”. In the first painting, a Jew holding a Torah is standing to the left of the cross, a woman with a baby holds out her arms to the man on the cross and Chagall falls face down, next to Jesus’ body, as if he had himself been crucified.

After the war, the Jews tend to see these crucifixions as a symbol of the suffering of the Jews, believing that they had no messianic meaning whatsoever. This is until the artist paints the cross behind Jacob’s ladder.

In the exhibition catalogue, Chagall quoted his friend Raissa Maritain, who converted to Catholicism: “The Old Testament was the harbinger of the New, and the New Testament is the fulfillment of the Old”.

This becomes clearer still in his depiction of the “Exodus” (1955). In this dark painting, the cross rises up in the top left-hand corner. In his famous “The Sacrifice of Isaac”, Jesus is carrying the cross, superposed in the background.

The red that covers the figure of Abraham suggests the idea of a blood sacrifice. That image of Isaac prefiguring Christ even appears in the tapestry that he did for the Parliament of the Knesset in Jerusalem.

MAN OF SORROWS

The account of the Passion not only occupies a large part of the gospels, it is already announced in the Old Testament. Jesus is presented as the Man of Sorrows announced in Isaiah 53:3.

Christ had known suffering beforehand, but in the garden of Getsemaní “he began to be sorrowful and troubled.” (Matthew 26:37), saying: “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death.” (v. 38). In contrast with the tranquility and peace of the upper room, Jesus is alarmed at the horrible perspective of unparalleled torment, which overcomes him.

The death of Jesus is not like Socrates’ drinking of the poisoned cup; his attitude is not serene and calm. The heroes that the Jews admired, such as the Maccabeans, faced up to death with defiance, presenting their members to be amputated.

Christ however is agitated and in utter agony (Luke 22:44), asking his Father whether there is any way of avoiding death (v. 42). What is the reason for all these “prayers and petitions with fervent cries and tears” (Hebrews 5:7)?

The death of Christ is different to any other, because he not only suffered terrible pain – three hours suffocating and bleeding to death –, but his physical death meant a spiritual death: what the Bible calls eternal death, the curse of separation from God.

When he calls out saying “Why have you forsaken me?” (Matthew 27:46), he expresses the agony of a breach that occurred in the very heart of God. He did in fact, as the Apostle’s Creed says, descend to hell.

SURRENDER AND SUFFERING

Jesus entered the darkness so that we did not have to go through it. The physical pain that we feel cannot be compared with the spiritual experience of cosmic abandonment that Christ suffered.

On the cross he suffered a pain that exceeds anything that we can know or bear. That is why Christianity is the only faith in the world that proclaims that God became man to experience our despair, loneliness, rejection, anguish and death first hand.

Why does God allow suffering? We do not have the answer to that question, but in the cross of Christ we at least have the assurance that he is not indifferent to our pain. God carries our misery.

He is truly Emmanuel – God with us–, even in our darkest hour. In his resurrection we know that our suffering is not in vain. His victory over death, not only brings us consolation but also announces the restoration of life.

We look forward to a new heaven and a new earth, where death, sorrows, cries and pain will be no more (Revelation 21:4), because God himself will be with us, drying every tear. It will be the renewal of all things, when the Son of Man takes his seat on the throne of glory (Matthew 19: 28). Creation will then dance, as in Chagall’s paintings.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o