Burnout among mission workers is on the rise. The repercussions are far costlier to the team, family, marriage, and ministry, and negatively impact the gospel witness.

![Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/66140bdce110b_LGABurnout940.jpg) Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

Photo via [link]Lausanne Movement[/link].

As a care provider, I should have seen it coming, but I did not. My normally energetic, vibrant, and accomplished wife was experiencing multiple life-altering symptoms that did not make sense to us.

She went from being a well-spoken, highly capable, and outgoing ministry leader and teacher to being unable to complete full sentences or make simple decisions. She was experiencing bouts of memory loss and mood swings.

In general, she was unable to function in her daily life and it was affecting us all.

After consulting with a therapist, she was diagnosed with severe burnout. The struggle for recovery led our family down a road of learning to understand the importance of a good theology of work, the importance of rest and rhythms, and how destructive burnout can be.

Fortunately, we are now on the recovery side of burnout and our life and ministry is better for it. This experience led me to research and write my dissertation on burnout among missionaries and mission sending organizations, eventually specializing in burnout as a member care trainer and provider.[1]

Burnout among missionaries is a growing phenomenon. A Barna statistic estimates that every month, approximately 1,500 North American ministry workers (pastors and missionaries) leave their work, due in part to burnout.[2]

At a whopping USD 500,000 price tag for recruiting, preparing, launching, and sustaining a ministry worker on the field for the first four years,[3] the cost of attrition due to burnout is astronomical.

However, the cost of burnout is not only monetary. Burnout affects families, teams, supporters, friends, and the advancement of the gospel.[4]

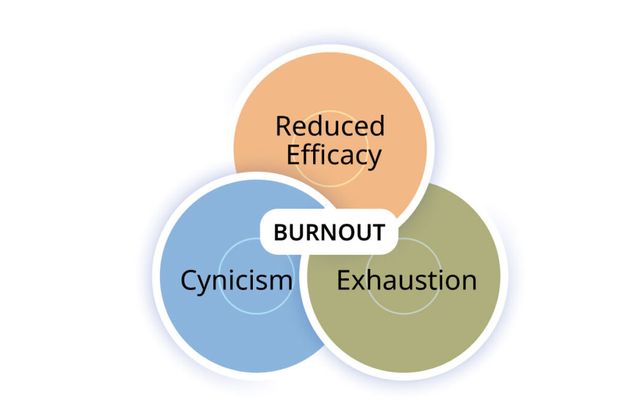

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is a syndrome resulting from unmanaged workplace stress. It is characterized by three main manifestations: exhaustion, cynicism, and reduced professional efficacy acting in conjunction.[5]

Exhaustion occurs when there is a lack of physical, emotional, mental, or relational resources to cope with or complete a task.

Cynicism is manifested when emotions take over resulting in an increased negativity toward work and people related to the work.

Professional efficacy is diminished as a sense of ineffectiveness and a felt lack of accomplishment.

A person might be exhausted or feel overworked, but exhaustion by itself does not constitute burnout.

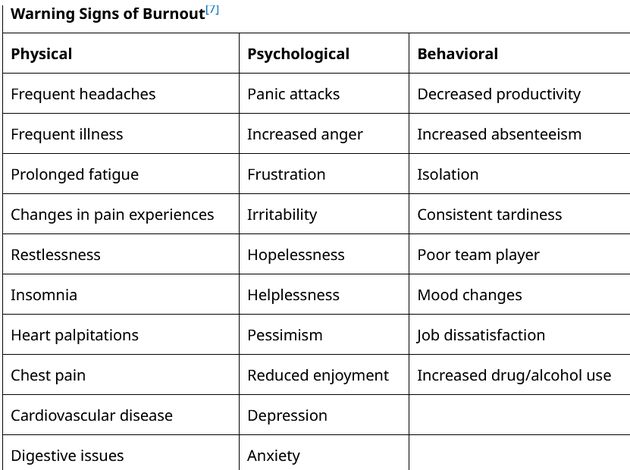

Likewise, a worker may be showing signs of negativity or cynicism, but that is not in and of itself an indicator of burnout. It is a combination of all three components which can be identified as burnout and causes people to begin to shut down physically, mentally, emotionally, relationally, and even spiritually.‘When somebody’s burned out, they are done. I mean, they can’t even handle how to get through the day anymore.’[6] The warning signs of burnout are many, but it is important to note that there are generally three main components: physical, psychological, and behavioral.

In addition to these signs, they may have difficulty in remembering things or making decisions, and experience feelings of failure and defeat.

Often, the person experiencing burnout is unaware of their condition and requires external intervention to recognize and name what is occurring.

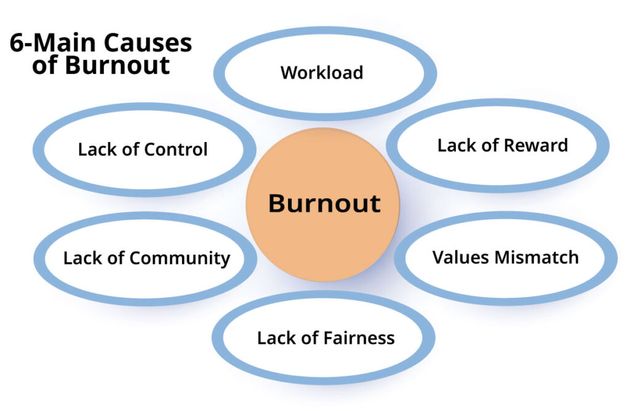

Maslach and Leiter have identified six major areas of concern that influence burnout among mission workers.[8]

A lack of control can occur in various ways for mission workers. Examples include:

Loss of autonomy and a lack of authority to control the work or decisions made for the ministry.

Lack of voice in the decision-making processes of the ministry, team, or their mission organization.

Feelings of being manipulated by decision-makers and those in authority.

Success metrics put in place by mission agencies or sending churches that are incongruent with local culture and context, or that focus on production and workload.

Role changes without proper preparation and vetting causing ambiguity, confusion, and role conflict.[9]

A lack of reward results when work is devalued due to insufficient recognition or negative reinforcement.[10]

Depending upon cultural context, rewards and fruitfulness from successful discipleship, evangelism, and other ministry efforts may be a long time coming or even non-existent.

There can be a feeling among mission workers that the work is never finished and that it is difficult to quantify success, which can lead to feelings of inefficacy. Oftentimes, a desire to see fruit and be rewarded for ministry efforts can supersede the desire for money or advancement.[11]

Values mismatch or conflict can arise when there is a disconnect between the values of the worker and the organization, or a discord between their worldview regarding work and the reality of daily life in their ministry context.

This can cause cynicism, demotivation, inefficacy, and misaligned workload. Values are essential for people to experience a deep relationship with their work, and when the values of the organization and the worker are mutually compatible, they can result in meaningful engagement of the worker and their role.[12]

Work overload can present itself in many ways. Some examples include:

Limited time, money, or staff to supply mission workers with the needed tools and support to complete their work effectively, resulting in added hours and workload.

Workers expecting too much from themselves and others and taking on a much heavier workload than is realistic for their abilities and resources.[13]

A self-worth and identity derived from work and performance.[14]

‘There is no work-life balance, unrealistic expectation, unprotected family time, not enough time with the Lord, lack of Sabbath, workload exhaustion, cultural and language adjustment, organizational perceptions that are not always supportive, spiritual warfare, family and personal illness, aging parents, difficulty in fundraising, homeschooling, relationship challenges, conflict . . . .

We live in a culture to perform . . . and performance trumps health. Numbers and productivity and getting the job done as opposed to being. We focus on doing more than being, and burnout is driven by that unhealthy focus.’[15]

There is often a breakdown in community when mission workers launch to foreign fields. Ministry outreaches and recipients of ministry efforts become replacements and fill relationship voids.[16]

Having healthy community is a counterbalance to burnout. People need a place to mutually experience success, celebration, laughter, joy, and comradery.

Community also refers to a place where people can experience others with a shared sense of values. When addressed in a work environment, community refers to the relationships within the workplace as people relate to the level of conflict, comradery, teamwork, and social support within the environment.[17]

[destacate] Having healthy community is a counterbalance to burnout. People need a place to mutually experience success, celebration, laughter, joy, and comradery [/destacate] Fairness as it relates to burnout is categorized as the comparison of how someone is treated in the organization in contrast with others in the same organization. Organizations must have trust, transparency, and respect.[18]

Workers may experience unfairness as it relates to pay, benefits, workload, evaluations, disputes, promotions, and other factors.[19] Failure to address incompetence, neglect, or negative people in the organization can lead to feelings of unfairness, hostility, anger, and cynicism.[20]

While self-care practices are important to the prevention and relief of the symptoms of burnout, dialogue is needed among organizations and leadership to take a closer look at the practices and policies in place for care of mission workers in cross-cultural settings.

Historically, burnout has been a phenomenon that mission workers and their organizations treated when it occurred, if it was recognized at all.

A more effective approach would be to recognize the causes and effect change proactively, working toward prevention and creating a healthier and more resilient missionary workforce. Here are some suggestions toward prevention:

Develop a baseline and yearly check-up for mission workers and staff regarding burnout health using some of these tools:

Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI)[21] to determine where workers are on the burnout continuum.

Areas of Worklife Survey (AWS)[22] to identify a worker’s perceptions of work in the six areas (control, workload, reward, community, fairness, and values).[23]

Conduct an organizational health survey developed and administered by the Best Christian Workplace Institute (BCWI)[24] to identify target interventions at the organizational and systemic level.

Embrace a culture of ongoing training and development at all levels of the organization. Both the leadership and mission workers should be trained in not only mission-related topics, but also on self-care, work-life rhythms, and signs and symptoms of burnout.

Give attention to training, selection and vetting processes, strengths-based placement, hybrid work roles, mentoring programs, proper onboarding and transition, and job description consultation to help diminish role confusion and conflict.

Reward the worker in an individualized manner more frequently, spontaneously, genuinely and sincerely, in a variety of appreciation modes.[25] This requires intentional communication and understanding of the work, context, goals, and achievements.

Through policies and leadership modeling, affirm and assure mission workers in keeping the sabbath, getting adequate sleep and rest, taking vacation and sabbatical to help maintain a sustainable workload and time of recovery to reduce exhaustion.[26]

Provide multiple opportunities and modalities for community building through regional and organizational gatherings, retreats, Bible study groups, celebrating together (even if remotely), communicating challenges, and praying together.

Constant communication between the field and home office, ensuring transparency between the office and mission workers with clear guidelines and confidentiality, and keeping people well informed are all trust builders for organizations and their mission workforce.

Provide training on supervision, mentoring, feedback, and appropriate goal setting.[27]

Value workers’ input into their roles as those who have decision-making input into their roles can experience reduced exhaustion and higher levels of efficacy.[28]

Burnout among mission workers and sending organizations is on the rise. While the loss or debilitation of a mission worker is quite costly financially, the repercussions are far costlier to the team, family, marriage, and ministry, and negatively impact the gospel witness.

Changes in systemic issues that are contributing to burnout, as well as changes in the way burnout is perceived among workers and leaders both need attention.

With some preventative measures in place and some attention to policies and procedures, mission sending organizations could affect great change toward the health of their workers and create more conducive environments for sharing the love of Christ with the nations.

Billy Drum, Director of Member Care Services at La Posada Training and Care (Spain), (www.laposadaspain.com), has served with TMS Global since 2007.

Billy and his family served in Latin America for several years, focusing on community development and education outreach. They moved to Spain in 2013 where he focuses on leadership development and care ministries.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

Billy L. Drum, ‘Burnout Among Cross Cultural Workers: An Analysis of Systemic Issues That Lead to Burnout Within Medium Sized North American Mission Organizations’ (MA Member Care diss., Redcliff College, 2021), https://www.scribd.com/document/681117359/Burnout-Among-Cross-Cultural-Workers-billy-Drum.

Christopher Ash, Zeal Without Burnout: Seven Keys to a Lifelong Ministry of Sustainable Sacrifice (Viborg, Denmark: The Good Book Company, 2016), 16.

Ken Harder and Carla Foote, Help Your missionaries Thrive: Leadership Practices that Make a Difference (Colorado Springs: GMI, 2016), 4.

Ash, Zeal Without Burnout, 24.

‘Burn-out an ‘occupational phenomenon’: International Classification of Diseases,’ World Health Organization, accessed 7 October 2020, http://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/burn-out/en/.

Anonymous P7, interview by Billy Drum, 31 May 2021.

Paula Davis, Beating Burnout at Work: Why Teams Hold the Secret to Well-Being and Resilience (University of Pennsylvania: Wharton School Press, 2021), 10-11.

Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter, The Truth about Burnout: How Organizations Cause Personal Stress and What to Do About It (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1997), 10-17.

Arnold Bakker et al., ‘Burnout and Work Engagement: The JD-R Approach,’ Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, no. 1 (2014): 389-411, doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091235.

Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter, ‘Areas of Worklife: A Structured Approach to Organizational Predictors of Job Burnout,’ in Emotional and Physiological Processes and Positive, Intervention Strategies (Research in Occupational Stress and Well Being, Vol. 3), eds. P.L. Perrewe and D.C. Ganster (Leeds: Emerald Group, 2003), 91-134, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1479-3555(03)03003-8. Brenda Bosch, Thriving in Difficult Places, Volumes 1, 2, & 3 (Pretoria, South Africa:Self-Published 2014), 82.

Maslach and Leiter, ‘Areas of Worklife,’ 91-134.

Maslach and Leiter, The Truth about Burnout, 16. Davis, Beating Burnout at Work, 54.

Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter, ‘Reversing Burnout,’ Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2005, https://ssir.org/articles/entry/reversing_burnout. Rob Hay et al., Worth Keeping: Global Perspectives on Best Practice in Missionary Retention (Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2007), https://www.everand.com/book/566434428. Bosch, Thriving in Difficult Places, Volume 2, 67.

Hay et al., Worth Keeping.

Anonymous P3, interview by Billy Drum, 14 April 2021.

Henry Cloud and John Townsend, Boundaries: When to Say Yes, When to Say No to Take Control of Your Life (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1992).

Christina Maslach, ‘Job Burnout: New Directions in Research and Intervention,’ Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(5), (2003): 189-192, doi:10.1111/1467-8721.01258.

Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter, ‘New Insights into Burnout and Health Care: Strategies for Improving Civility and Alleviating Burnout,’ Medical Teacher, 39(2), (2017): 160-163, doi:10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918.

Ronald Koteskey, Psychology for Missionaries (Wilmore, KY: GO International, 2014), https://www.missionarycare.com/psychology-for-missionaries.html.

Maslach and Leiter, ‘New Insights into Burnout and Health Care,’ 160.

Christina Maslach et al., ‘Maslach Burnout Inventory™ (MBI),’ accessed 11 December 2023, https://www.mindgarden.com/117-maslach-burnout-inventory-mbi

Michael P. Leiter & Christina Maslach, ‘Areas of Worklife Survey,’ accessed 11 December 2023, https://www.mindgarden.com/274-areas-of-worklife-survey

Maslach and Leiter, ‘Areas of Worklife,’ 102. Maslach and Leiter, The Truth about Burnout, 155.

‘Increase Kingdom Impact,’ Best Christian Workplaces, accessed 11 December 2023, https://workplaces.org/.

Gary Chapman and Paul White, The 5 languages of Appreciation in the Workplace: Empowering Organizations by Encouraging People (Chicago: Moody Publishers, 2019), 132-147.

Maslach and Leiter, ‘Areas of Worklife,’ 96.

Bosch, Thriving in Difficult Places, Volume 1, 83. Hay, et al, Worth Keeping.

Maslach and Leiter, ‘Areas of Worklife,’ 97.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o