Far too often in the mission world, we mistake burnout as the height of service to God, but effective service cannot be done by a burnt out, shrivelled body, mind, or soul.

![Photo: [link]Anthony Tran[/link], Unsplash CC0.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/65f96fc0d4896_anthonytrancof940.jpg) Photo: [link]Anthony Tran[/link], Unsplash CC0.

Photo: [link]Anthony Tran[/link], Unsplash CC0.

Member care and self-care are not new concepts. However, marrying the two has been a more recent discussion, which gathered pace during the COVID pandemic.

In this article, we will consider what member care and self-care are, some of the resistance to self-care, and how member care can seek to promote better self-care practices amongst missionaries.

Put simply, the Global Member Care Network (GMCN) defines member care as follows: ‘Member care is the ongoing preparation, equipping and empowering of mission personnel for effective and sustainable life, ministry and work.’[1]

Debate about whether the term is good enough to catch the breadth of the practice is ongoing. It is recognized that some mission organizations now use the term ‘staff care’, or even ‘staff care and wellbeing’ rather than member care.

An informal survey on the GMCN Facebook group in 2021, which has over 1,000 members, showed that whilst the term ‘member care’ is not ideal, there was no consensus on a preferred choice.

Whichever terminology mission organizations choose to use, the key elements are the care and resources provided to a missionary to enable them to thrive.

The World Health Organization defines self-care as ‘the ability of individuals, families and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health worker.’

We will look only at the self-care of an individual. It is that which a person does themselves, to enable them to be healthy enough in mind, body, and spirit to perform the functions that are required of them.

Ohanian goes further: ‘Self-care ensures that one will thrive and flourish as opposed to merely survive and cope. Self-care is the unseen root system, deep, nourished, expanding, of a strong, resilient, blossoming tree.’[2]

This imagery is very helpful in considering that self-care is not an easy fix but requires roots, time, and regular feeding. Having defined the terms, we will now explore the increase in awareness of the importance of self-care seen during and after the COVID pandemic.

Self-care became a more talked about concept during the recent COVID pandemic. There were many articles about how people could care for themselves and ensure that the lockdowns and bad news from across the globe did not negatively affect their physical and mental health.[3]

The rise of focus on self-care during the pandemic was in part due to the unavailability of the other sources and places where people might usually receive support and care and also extra time freed up by the lack of commute and travel.

A study in 2021 found that whilst there was a significant risk of anxiety and depression, 39 percent of the participants either started or increased their self-care and 23 percent invested in self-care for the first time.[4]

Discussion about self-care and self-care practices has, therefore, cemented itself within common parlance. Let us now look at the relationship between self-care and member care.

There are several models of member care in literature including Dodds and Dodds SPARE-O model[5] and Harry Hoffmann’s Pyramid of Care[6] (developed from Warlow’s Christian Wholeness Framework).

However, most of these do not specifically mention self-care and place little emphasis on the actions of the individual, instead emphasizing the care and support offered to individuals by the people and systems around them.

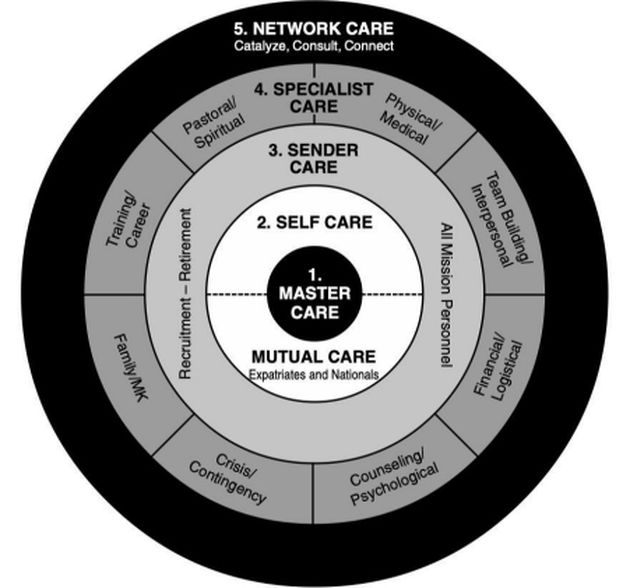

Perhaps the most well-known model which does mention self-care is that of Kelly O’Donnell and Dave Pollock as illustrated in this diagram.[7]

Each of the five spheres are permeable, and care can flow between them. The sources of member care are included, eg senders, such as sending church or mission organization, as are the types of care, eg family and TCKs (Third Culture Kids).

At the core of the model is Master Care, in recognition that God is the master, and it is from him that we receive strength. And it is him whom we serve.

The second sphere includes mutual care (from relationships around us) and self-care. Thus, the blending of the two concepts, member care and self-care. Having taught on the topic of member care for several years,

I would reflect that one of the weaknesses of this model is that self-care is not a sphere by itself. By joining it with mutual care, it is watered down and not given the attention that it deserves.

Rather than encouraging missionaries to take some responsibility for themselves and their own wellbeing, it reinforces a mindset that member care is received. It has a tendency to focus on what others can provide.

This leads us to consider why self-care in mission can have a negative response.

I recently led a retreat and webinars on the topic of self-care. Whilst many were keen to learn about how to improve their own self-care, a number of questions and comments were raised: Isn’t self-care selfish? I’m already too busy; I don’t have time for self-care. Self-care is the opposite of living by faith. We’re called to be living sacrifices, so self-care cannot be biblical.

In Romans 12:1 (NIV) Paul says, ‘Therefore, I urge you, brothers, in view of God’s mercy, to offer your bodies as living sacrifices, holy and pleasing to God—this is your spiritual act of worship.’

These verses are used to argue that rather than showing care to ourselves, we should be offering our lives as a sacrifice to God.

The topic of sacrifice and how missionaries tackle the difficult issues of risk and suffering are well documented[8] and indeed in my teaching on the MA in Member Care and MA in Staff Care and Wellbeing at Redcliffe College and All Nations Christian College, respectively,

I have emphasized the need for new missionaries to develop their own theology of suffering and risk before they arrive on the field.

The stories and images of Christian martyrs play an important role in Christian mission, but they can also cause a skewed theology of ‘it’s better to burn out than rust out’.

Alongside the consideration of risk, we need to recognize that the call to consistently show up in what Eugene Peterson calls ‘a long obedience in the same direction’[9] can be a costly calling.

Rather than self-care being selfish and a direct opposite of living as a sacrifice, I believe that self-care is an important tool in the missionary tool kit. In John 7:37, Jesus invites those who are thirsty to come to him and drink.

This is not passive but requires action on behalf of the one with thirst. In John 1, there is another invitation as Jesus calls the disciples to ‘come’ so that they could see.

Perhaps the most beloved of verses for the member care practitioner is Matthew 11:28-30 (MSG): ‘Are you tired? Worn out? Burned out on religion? Come to me. Get away with me and you’ll recover your life. I’ll show you how to take a real rest. Walk with me and work with me—watch how I do it. Learn the unforced rhythms of grace. . . . I won’t lay anything heavy or ill-fitting on you. Keep company with me and you’ll learn to live freely and lightly.’

This, to me, is an invitation to care for oneself by coming to God. A more obvious biblical example of self-care would be Jesus himself, who gave himself time and encouraged his disciples to rest and pray in the midst of a life of self-sacrifice (Matt 14:13; Mark 6:30-32).

As Ohanian says, ‘Self-care is neither selfish nor egotistical, but a wise preventative and self-respecting practice for anyone who desires to remain in their role of care and service.’[10]

Far too often in the mission world, I believe that we mistake burnout as the height of service to God. We see burnout as a badge of honour. However, effective service cannot be done by a burnt out, shrivelled body, mind, or soul.

We should put our efforts into helping a missionary serve well and serve faithfully, without serving until they can serve no more due to burnout.

There is a road back from burnout to service, but it can be long and difficult, and it is far better to prevent burnout than repair it.

Member care is multi-faceted, and there are many preventative and curative ways in which a member care practitioner can support the missionaries they are responsible for. An essential preventative tool we must recommend is that they practice self-care. This should be non-negotiable.

How can we facilitate self-care in others? There are spiritual, physical, emotional, cognitive/creative, and social/systemic aspects which we can encourage.[11] Examples are numerous and varied.

Taking the physical aspect, we could encourage attention to sufficient and good sleep, eating more healthily, exercising a little more, and talking to a doctor if stress symptoms are evident, for example.

The new field of environmental neuroscience is already proving that exposure to nature is essential for our brains.[12] Green (vegetated) and blue (moving water) environments can be associated with a reduction in stress, but now it seems that exposure to the great outdoors benefits cognitive function too.

Nature activates our ‘resting’ state which then encourages calm and wellbeing. Fractal patterns (naturally occurring patterns such as leaves on a succulent plant or a snowflake) are also known to help our brains.

So simply encouraging a missionary to take a short walk outside in nature[13] would be an excellent way to assist them in their self-care.

The widespread engagement with self-care during the pandemic has highlighted the power and potential of personal responsibility for wellbeing.

Member care practitioners can harness this learning by revisiting the balance between personal responsibility and external intervention in missionary care.

It requires a theological as well as a sociological and practical element to recognize that meaningful self-care is not a selfish practice, but an essential part of a missionary’s tool kit and one which the member care practitioner should encourage.

Sarah Hay (Chartered MCIPD) is the HR and Member Care Manager of European Christian Mission Britain, visiting lecturer (and former co-leader) for MA in Staff Care and Wellbeing at All Nations Christian College and former Course Leader, MA in Member Care, Redcliffe College.

This article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of the Lausanne Global Analysis and is published here with permission. To receive this free bimonthly publication from the Lausanne Movement, subscribe online at www.lausanne.org/analysis.

’The Global Member Care Network Member Care Definition’ ,

‘Self-care interventions for health,’ World Health Organization, accessed 29 November 2023,

Nairy Ohanian, ‘Self-Care,’ unpublished paper,

‘Self-care tips during the COVID-19 pandemic,’ Mayo Clinic Health System, 7 April 2020,

Amelia Fiske et al., ‘Impact of COVID-19 on patient health and self-care practices: a mixed-methods survey with German patients’, BMJ Open, Vol. 11 Issue 9, 2021.

Lois Dodds & Lawrence Dodds, Selection, Training, Member Care and Professional Ethics: Choosing the Right People and Caring for Them with Integrity ( Liverpool, PA: Heartstream Resources, 1997).

Harry Hoffmann, ‘Connecting and Resourcing Member Care Practitioners Worldwide: The Global Member Care Network’, Evangelical Missions Quarterly, 56(1), 2020.

Kelly O’Donnell, ed., Doing member care well: Perspectives and Practices From Around the World (Pasadena:William Carey Library, 2002).

Anna E. Hampton, Facing Danger: A Guide Through Risk (New Prague MN: Zendagi Press, 2016). Charles A. Schaeffer and Frauke C. Schaeffer, Trauma and Resilience, A Handbook (Chapel Hill, NC: Frauke C. Schaefer, MD, Inc: 2016).

Eugene Peterson, A Long Obedience in the Same Direction (US: Inter-Varsity Press, 2000).

Ohanian, ‘Self-Care’.

See the SPECS model outlined by Hawker and Horsfall in Tony Horsfall and Debbie Hawker, Resilience in Life and Faith: Finding your strength in God (Abingdon: The Bible Reading Fellowship, 2019).

Sam Pyrah, ‘The nature cure: how time outdoors transforms our memory, imagination and logic’, The Guardian, 27 November 2023.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o