Europe is polycentric, not only on the cultural but also on the spiritual and religious level.

![Monument to the Geographical Centre of Europe in Polotsk, Belarus. / [link] Tranzit-by[/link], Wikimedia commons.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/656e4f5918d69_Polotsk940.jpg) Monument to the Geographical Centre of Europe in Polotsk, Belarus. / [link] Tranzit-by[/link], Wikimedia commons.

Monument to the Geographical Centre of Europe in Polotsk, Belarus. / [link] Tranzit-by[/link], Wikimedia commons.

When we talk about the role of Europe in the world in the past and today, whether in the area of economics, politics, colonisation, science and technology, or with respect to the missionary endeavours to spread the Christian faith, we are tempted to see Europe as a whole, as a single centre of power and influence amidst the other world ‘powers that be’.

This view however is quite mistaken.

Viewed from the outside the outlook of all European countries is quite similar, as compared to other regions of the world, so much so that they are collectively called ‘European’.

This similarity is also felt by the Europeans themselves despite their differences. There is among these peoples a widespread sense of belonging to a larger whole called ‘Europe’.

Usually this idea of ‘Europeanness’ is defined in terms of common cultural and religious roots, a common historical experience, and common values such as democracy and human dignity.

What we call ‘Europe’ is in fact a conglomerate of several peoples or ethnic identities, living in several nations, each of them with its own language (or languages, as in Belgium or Switzerland), its own history and culture, its own army, and its own national institutions and enterprises. They are all ‘European’, but each of them in their own particular way.

Throughout history there have been several attempts to unite all the European peoples under one crown, in one empire, under one political banner, at the cost of much suffering and bloodshed. All these attempts have failed.

[destacate]What we call ‘Europe’ is in fact a conglomerate of several peoples or ethnic identities, living in several nations, which are all ‘European’, but each of them in their own particular way[/destacate] The only successful project of unifying Europe to date is the process of integration that began after the Second World War, with the reconciliation between the former enemies France, Germany, and Italy.

Why could it succeed? Precisely because it did not depend on one centre of power. Instead of one nation trying to impose itself as the leader of the rest, several nations chose to work together for peace and prosperity on the basis of mutual agreement.

This was not a project of replacing the states by one superstate, but of a community of nations, working for the common good. They created supranational institutions of governance, but they remained sovereign in many areas.

Moreover, they agreed upon a number of common values to guide the process of integration, such as solidarity, subsidiarity, democracy, human dignity, and above all unity in diversity.

All of this is laid down in a series of European treaties. None of these treaties ever mention the term ‘polycentric’, but this term is quite appropriate to denote the model of governance that has been chosen to realise the European integration. This comes out in a number of ways.

Firstly, rather than being concentrated in a single capital city, the institutions of the European Union (EU) are seated in four different cities; the European Council as well as the European Commission and its administrative offices in Brussels, the European Bank in Frankfurt, the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg, and the European Parliament in Strasbourg. EU agencies and organisations have their locations across the Union.

[destacate]The only successful project of unifying Europe to date is the process of integration that began after the Second World War, with the reconciliation between the former enemies France, Germany, and Italy[/destacate] Furthermore, the presidency of the European Council of Ministers, where the main decisions are taken, rotates among the member states of the EU every six months. During that period, the capital of the presiding nation is the centre of Europe.

Similarly, every year the Council of Europe designates one or more cities on the continent ‘cultural capital of Europe’. Hereby, it aims to bring to light that Europe is truly polycentric in the area of culture and art. Every nation has its famous places of interest, together they constitute the richness of the European cultural heritage.

Following the same polycentric principle, the European institutions have adopted a policy of multilinguism. The EU has recognized 24 official languages, besides a number of regional languages.

The current Spanish presidency of the European Council has submitted a proposal to give three regional languages in Spain the status of official EU language (Catalan, Galician, and Basque).

Official texts are published in at least the major languages. Each European commissioner and each European MP have the right to publicly speak their own language, which they invariably do.

Thanks to a host of simultaneous interpreters, communication is possible in this modern Babylon.

Italian author Umberto Eco once said: ‘Europe is translation’, in order to emphasise that linguistically, Europe is polycentric. Instead of imposing one language for all, we have to translate each other’s languages to assure that every nation can make its own voice be heard.

Moreover, translation is the precondition of maintaining our diversity. And only through learning each other’s languages can we appreciate each other’s cultures, and work together for the common good, European-wide.

Even though English is becoming more and more dominant, the other languages resist. Huge funds are invested to keep all of them ‘alive’, in publishing, higher education and scientific research, the media, and the arts.

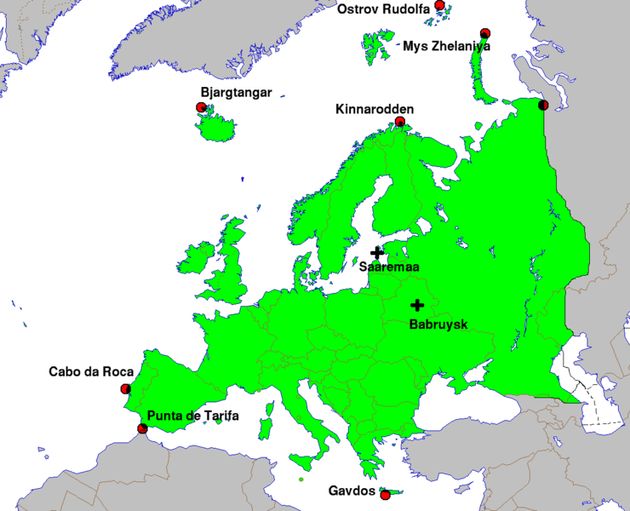

Even when it comes to defining it geographical midpoint, Europe appears to be polycentric. Where is the centre? Different answers are given, depending on where one draws the borders of Europe and on the method of calculating the middle.

Europe has never had a generally agreed upon midpoint. More than a dozen locations have been proposed to carry the title ‘centre of Europe’.

[destacate]Even when it comes to defining it geographical midpoint, Europe appears to be polycentric Where is the centre?[/destacate] In fact, there is a long history of determining the geographical centre of Europe, since the Polish astronomer and cartographer Szymon Sobiekrajski calculated that it was located in the town of Suchowola in modern north-eastern Poland (1).

Today, there is still no unanimity among geographers, but the number of serious candidates for the title is now reduced to three. One is the Hungarian village of Tallya, the second is a village on the island of Saaremaa in western Estonia, and the third one is Polotsk, near Lake Sho in Belarus.

In the midst of this confusion, one thing is sure. Whatever method one uses, one finds the midpoint always somewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, far away from the economic centres in the West, far away also from the political, administrative, and financial centres of the European Union.

Many Western Europeans are biased by the idea that their countries constitute the heartland of Europe, and that people in the east would do best to ‘catch up with us’. They should clean their spectacles and realise that they are simply not ‘in the middle’.

They are just the western half of the continent, rooted in Latin and Rome, besides the eastern half that is rooted in Greek and Byzantium.

I recall the words of the Orthodox metropolitan Mikhael Stakos in a speech for the Clergy-Laity Conference in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 2000, in which he severely criticised the Museum of European History in Brussels, created by the European Commission. The museum makes this history begin with the time of Charlemagne.

‘This is a limitation of our history and in insult to the European spirit’, said the patriarch. ‘Do not the Minoan culture of Crete, the Acropolis of Athens, and the Hagia Sofia of Constantinople (Istanbul) belong to all Europeans and to all Christians?’ (2)

His words remind us that Europe is polycentric, not only on the cultural but also on the spiritual and religious level.

This reality is amplified by the far-reaching demographic change that is taking place since the 1970s.

As a result of continuing immigration from outside Europe, and the higher birth rates of the ‘new stock Europeans’ as compared to those of the ‘old stock’ Europeans – to use the terminology of Philip Jenkins (3) – an increasing part of the population has a non-European ethnic and cultural background, and they are much more religious than the largely secularised old stock Europeans.

Instead of assimilating, many migrant communities develop a form of bicultural mix, so that there continues to be a difference with their ‘old stock’ surroundings.

How does this survey of polycentric Europe have a bearing on Christians in mission? By way of conclusion we would suggest the following four points.

[destacate]An increasing part of the population has a non-European ethnic and cultural background, and they are much more religious than the largely secularised old stock Europeans[/destacate] First of all, the need for a polycentric understanding of European societies, cultures, and religious communities.

Secondly, the importance of multilinguism in Europe. This is a real challenge for mission organisations that are increasingly dominated by English as the language of theological reflection, of mission conferences, and of communication between mission agencies.

This creates a linguistic power centre, which advantages native English speakers over those who have had to learn the language later in life, and which can easily marginalise or even bypass large sectors of the European cultural and religious realms.

And it leads to many blind spots. In this respect, there is much to be learnt from the policy of the European institutions.

Thirdly, the importance of recognising cultural and national diversity. ‘Europeanness’ comes in many variants. This is another challenge for mission organisations that are tempted to use one country as a base to ‘reach out’ to the rest, instead of creating real partnerships with people in other countries.

Here again, much can be learned from the experiences of the European integration project.

Finally, from a polycentric viewpoint, no church or organisation should feel marginalised, whatever their geographical location. Each one of them can take centre place in the communication of the Gospel in Europe, similar to the rotating presidencies and cultural capitals mentioned above.

Evert van De Poll is co-editor of Vista.

Vista is an online journal offering research-based information about mission in Europe. Founded in 2010, each themed edition covers a variety of perspectives on crucial issues for mission. Download the latest edition or read individual articles here. This article first appeared in the november 2023 edition of Vista Journal.

1. See for this history: Gardner, N. ‘Pivotal points: defining Europe’s centre’, in Hidden Europe (5), November 2005, p. 20ff.

2. Metropolitan Michael (Stakos) of Austria, The Contribution of Orthodoxy on the Course Towards a United Europe. Speech at the Clergy-Laity Conference, Constantinople,(Istanbul), 24 November 2000

3. 5. Philip Jenkins, God’s Continent, Oxford University Press, 2007

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o