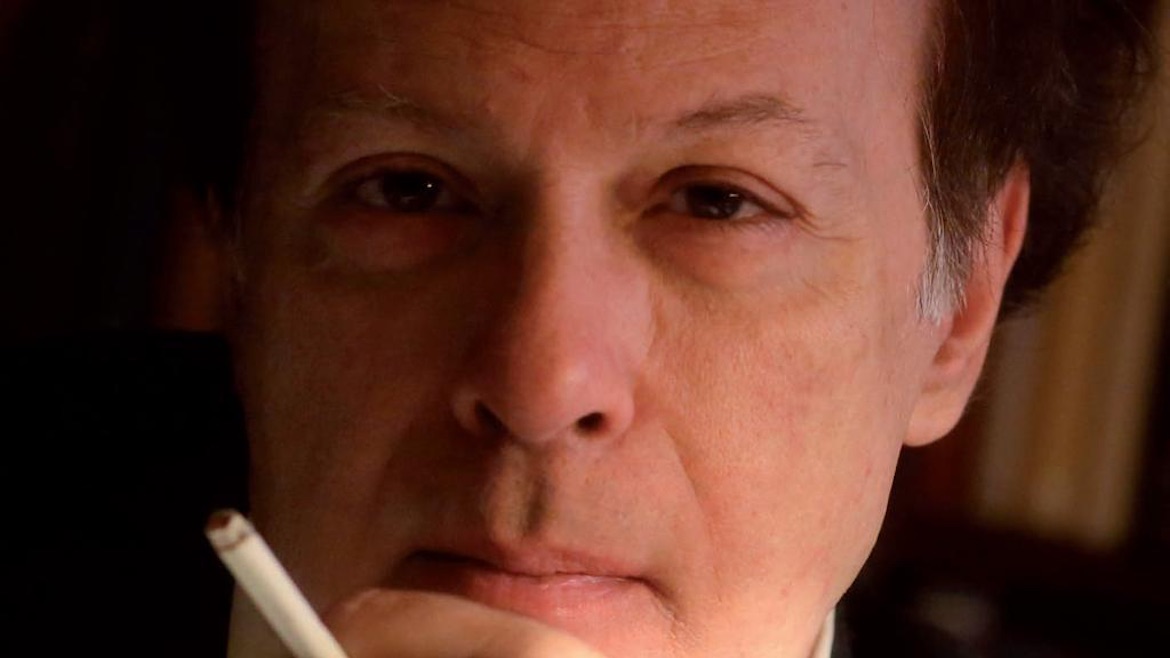

One of the best writers in Spain died recently. His sensitivity and tremendous capacity for observation painted a realistic image of how human beings are.

If there is a clear theme in the literature of Javier Marías (1951–2022) it is that appearances can be misleading.

If there is a clear theme in the literature of Javier Marías (1951–2022) it is that appearances can be misleading.

If there is a clear theme in the literature of Javier Marías (1951–2022) it is that appearances can be misleading. We have all been in the situation where we thought we knew someone until, suddenly, we discover something about them that we would have never imagined.

Like Javier Marías, I also think that we all have secrets, things that we keep hidden but, unlike him, I know that one day they will come to light, even though they are now covered by a veil of deceit and pretence.

We all have authors with which we have formed a special relationship. We no longer read their books for their literary value, but because there is an emotional bond that clouds our analysis and the way in which we value each of their specific books. Each of them gives us an entry into a world as personal as that of our own memory. That is my experience with the authors of what is now referred to in Spain as the “generation of the 80s”, and which include Javier Marías, Antonio Muñoz Molina and Javier Cercas.

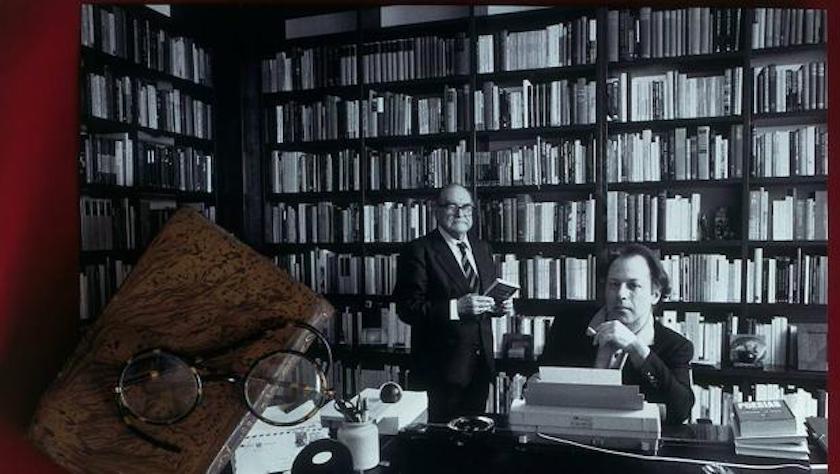

In the 1980s, I would see Javier Marías in the bus on my way to the Literature Faculty of the Complutense University in Madrid. He taught theory of translation there, having returned from Venice to live with his father, the philosopher Julián Marías. At that time, I was studying Dutch in the afternoons, after having first tried to combine a German course with my journalism degree. As neither of us ever learned how to drive – following a family tradition, I suppose, as our parents didn’t drive either – we travelled in on a bus that stopped at both our streets.

[photo_footer]

Javier taught theory of translation, having returned from Venice to live with his father, the philosopher Julián Marías.

[/photo_footer]

There has always been a strange relationship between literature and journalism. There are writers like Antonio Muñoz Molina that compel me buy the print edition of El País every Saturday for the simple pleasure of holding his articles in the cultural supplement in my hands. Javier Marías, in contrast, appeared much more cantankerous in his weekly article in El País Semanal, which I avoided reading so that I could continue admiring his literature. Unlike many, I appreciated Marías for his books, rather than his articles.

Some people can’t stand Marías’ books. They struggle to understand his obsessions and find the repetition of the thoughts of his characters insufferable. I don’t know why, but I have a strange weakness for him. I only have to read the first lines of one of his books and I am hooked. I reread his paragraphs, amazed by his style, sensitivity and tremendous capacity for observation.

Literature has that capacity to enter our minds and awaken our thoughts. What for some is repetition in authors like Marías, for others is an expression of their own mental hesitations, and the thoughts that we keep to ourselves. A question that Marías often asks himself is what would happen if we said what we really thought. I, like him, think that it would be disastrous.

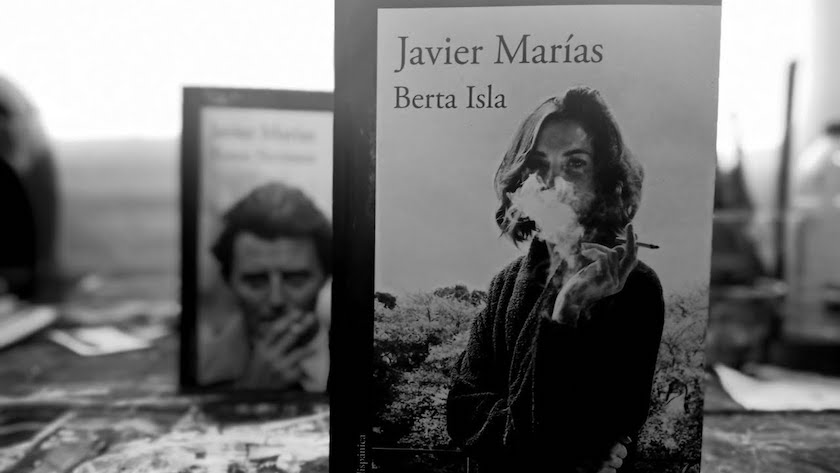

[photo_footer] Marias’ love and espionage stories speak of the secrets that we all keep. [/photo_footer]

It is impossible to conceive of the narrator of a story like Thus Bad Begins without thinking of “young Marías”, as Juan Benet called him when Javier started writing, aged seventeen. In that novel, the relationship between the main character (Juan De Vere) with a film director and his wife (Eduardo Muriel and Beatriz Noguera), reminded Benet – whom Marías credited for having changed the face of twentieth-century Spanish literature – of the time that Marías had spent in Paris with his uncle Jess – his mothers’ brother, who produced porn and horror films with his partner, Lina Romay. Thus Bad Begins is a novel of initiation – what the Germans call a Bildungsroman – a story tracing a formative period of life.

Javier comes from an exceptional family. His father, Julián, was probably the most brilliant disciple of the Spanish philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, but he found a Christian significance that his master never found. Even though he was a monarchist, he was imprisoned as a republican when Franco came to power. He represented the “third Spain”: neither Francoist nor republican – history’s great loser, which no one has sought to vindicate. His mother, Dolores Franco, was an intelligent and sensitive woman, who had great trouble in publishing her book España como preocupación (Spain as concern) during the dictatorship. She died young of cancer, in 1977, and her family was never the same again. Those of us who knew Julián, remember him as a widower wishing to join his wife in the resurrection. And Javier was so close to her that he would leave any bed to look for a phone box from which to call his mother first thing in the morning.

In his book The Dark Back of Time, Javier spoke of a brother that died in childhood. He was the fourth of five sons, but it was the eldest who died as a child. Javier himself was only 70 when he died of pneumonia. I don’t know if genius is genetic, but each of his brothers is brilliant in their own right: Fernando is a renowned art historian, associated with the Prado Museum and specializing in Velazquez; Miguel is an economist who has become one of the most impressive film critics that Spain has ever seen; and Alvaro is a musician who specializes in the Baroque period, putting down in writing what he is not able to say out loud, as he is known to be a man of few words.

[photo_footer] Javier was the fourth of five sons in a brilliant family. [/photo_footer]

At the beginning of the 1980s, Spain was still in its transition towards democracy. Efforts were made to forget about the civil war and a series of changes were introduced that would lead to laws on divorce – promoted by the Union of the Democratic Centre of Fernández Ordóñez. The story about the unhappy couple in Thus Bad Begins is difficult to understand without knowing that, back in the day, people got married for ever. This story was told by Javier, who remained a bachelor until very late and was the son of a very close couple, even though his mother died young.

The Transición period in Spain was a time of “coat turning”, when staunch Franco supporters presented themselves as democrats. Some people who had, at the time, informed on those who were not sufficiently loyal to Franco’s regime, went so far as to welcome the end of the dictatorship, claiming to have liberal ideas – as in the case of Camilo José Cela. Meanwhile, Javier’s father was looked down on as being too right wing, even though Franco had put him in prison on false accusations for being a republican. This is why Javier Marías declined the Spanish Literature Award for Narrative in 2012 for The Infatuations, saying: “If my father did not deserve a National Award, I don’t either”.

In The Infatuations the paediatrician Van Vechten covers up his actions during the dictatorship, pretending to have helped its victims. The rapid revision of many a biography not only buried the past under a law of silence but also conjured up supposed anti-Franco acts of heroism. Thus, Javier Cercas asks himself in The Impostor how Enric Marco was able not only to claim to have been a survivor of a Nazi concentration camp but also to become, at the end of the 1970s, Secretary General of an anarchist trade union under the Spanish National Confederation of Labour (CNT) on account of his imagined activities under the dictatorship. The whole country seemed to be living a lie.

It should come as no surprise that the transition period in Spain was based on concealment and lies. All our lives are based on the self-deception of lies repeated so often that end up seeming to be the truth. As the Cercas discovers, “fiction saves, but reality condemns”. It is as if we “needed fiction in order to keep on living”. In Cercas’ story, the character of Marco, like everyone else, invented an anti-Franco past in order to be able to stand himself. The author concludes that “he is, in some way, what we all are”.

[photo_footer] In his last two books Marías introduces us into the reality of a couple who have become strangers to one another. [/photo_footer] Stories like The Impostor and Thus Bad Begins speak of “our insatiable and humiliating need to be loved, accepted and admired”, Javier Cercas has said. “They show how we are all putting on an act to a certain extent”, since we are “all novelists of ourselves”. Lies come so easily to us “and we offer others an image that isn’t the true one”. The problem is that, “at the end of the day, we have to face up to the facts”.

When Muñoz Molina tries to understand the assassination of Martin Luther King, he goes back to the Lisbon of the 1980s, where the criminal in his book Like a Fading Shadow and he himself lived when he wrote the book Winter in Lisbon. What he discovers there is his own gilt, the lies to his wife and the distance he created with his new-born son, trying to escape humdrum reality and the weight of family responsibility, all making him wish for a different life.

Molina thus identifies himself with Martin Luther King and his secret lover, Georgia Davis, who follows him from city to city and was with him on his last night at the Lorraine Motel. This is something that Christians prefer not to acknowledge, because the honesty of such accounts contrasts with our pretensions to be better than everyone else, free from all unfaithfulness. We believe that our spiritual language can cover up the reality of who we are, whereas the Word of Truth reveals our imposture.

Marias’ love and espionage stories speak of the secrets that we all keep. In his last two books, Berta Isla and Tomás Nevinson, he enters the reality of a couple who have become strangers to one another. They display the kind of opacity that means that we can never be sure of what the other person is thinking and who they really are.

The unfortunate couple in Thus Bad Begins tries to cover up a past that cannot be undone, even though it has not yet become public knowledge. When the story becomes predictable, full of empty dialogues and banal issues, the truth is revealed, sequestered by spurious interests. It is concealed for legitimate reasons of protection and to prevent the consequences of revealing it, and the resentment that not having known of it earlier could cause.

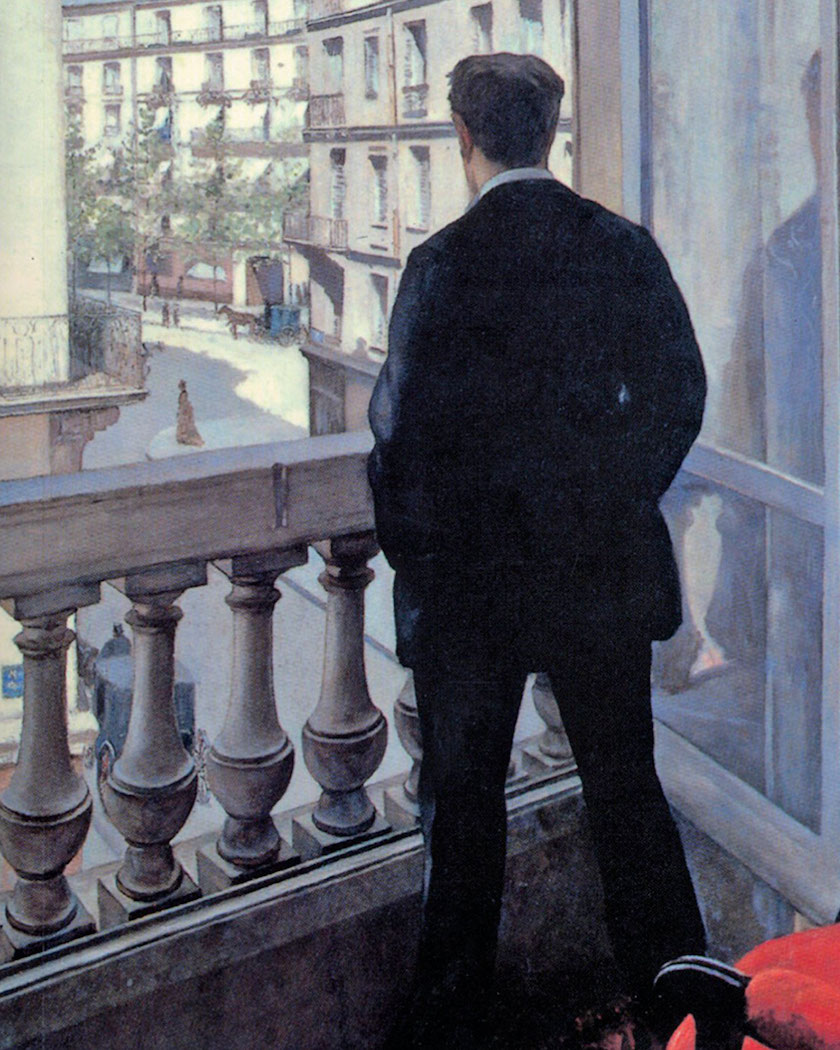

Jesus says : “there is nothing hidden that will not be disclosed, and nothing concealed that will not be known or brought out into the open.” (Luke 8:17). Javier Marías’ books are about truth and lies, secrets and their revelation, the dilemma between knowing those secrets and discovering them, and knowing them and keeping quiet. They express the fear of life being destroyed by our secrets – secrets which at the first opportunity can become devastating cataclysms.

[photo_footer] Javier Marías’ books are about truth and lies, secrets and their revelation, the dilemma between knowing those secrets and discovering them, and knowing them and keeping quiet. [/photo_footer]

The Bible teaches us that only the Author of Life knows us better that we know ourselves. We can’t fool Him. He knows the truth about our lives. And that is why He alone can judge us justly. Some believers, however, believe that they have the absurd mission to discern who will be cleared, according to the fruits and evidence that they think that they can see based on mere external appearance. Ignorance is decidedly insolent. We need to be more humble and recognize that “the Lord recognizes his own” (2 Timothy 2:19).

God’s law is like a mirror (James 1 :23), showing us what we are. The temptation is to look away and pretend that we aren’t as bad as others, but in God’s eyes, we are all found wanting (Romans 3:20). We can’t fool Him. He knows the truth of what we do, think and say.

Are we who we say we are ? Why do we do what we do? “For God will bring every deed into judgment, including every hidden thing, whether it is good or evil” (Ecclesiastes 12:14). He knows what is in our hearts (1 Samuel 16:7) and he listens to our words (Matthew 12:36). He hears and sees everything. We are not alone with our secrets.

As R.C. Sproul says: “There are many things in my life that I do not want to put under the gaze of Christ. Yet I know there is nothing hidden from Him. He knows me better than my wife knows me. And yet He loves me. This is the most amazing thing of all about God’s grace. It would be one thing for Him to love us if we could fool Him into thinking that we were better than we actually are. But He knows better. He knows all there is to know about us, including those things that could destroy our reputation. He is minutely and acutely aware of every skeleton in every closet. And He loves us.”

José de Segovia, theologian, journalist, and pastor of an evangelical church in Madrid (Spain).

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o