Well before the 1979 Campus Crusade “Jesus” film, based on the literal words of Luke’s Gospel, Pasolini discovered that in Catholic Italy very few had read the Gospel of Matthew.

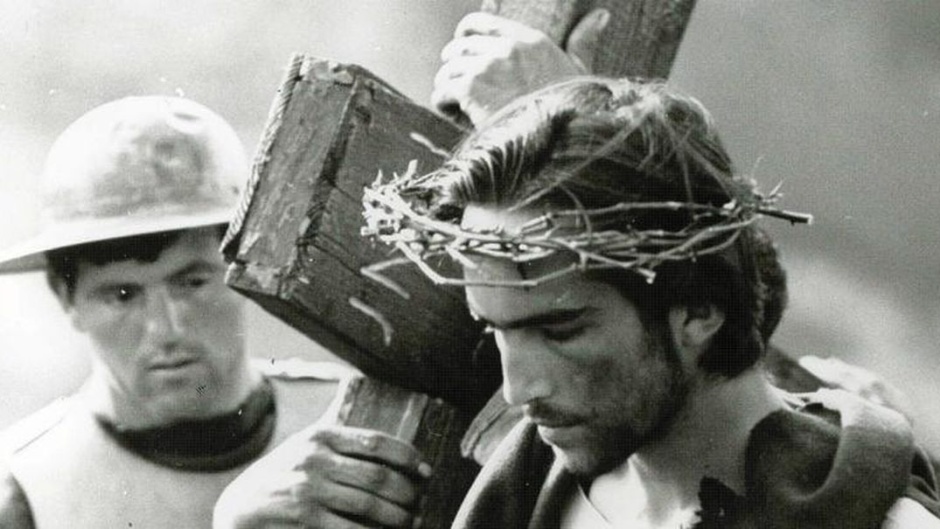

The literal text of the Gospel of Matthew is brought to the screen in a modest black and white production that won the special jury prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1964. / Images: Scenes of the film.

The literal text of the Gospel of Matthew is brought to the screen in a modest black and white production that won the special jury prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1964. / Images: Scenes of the film.

Every time that a new film about Jesus is made, the question that Christians tend to ask themselves is whether it is faithful to the Gospels. To start with, few films use Jesus’ words.

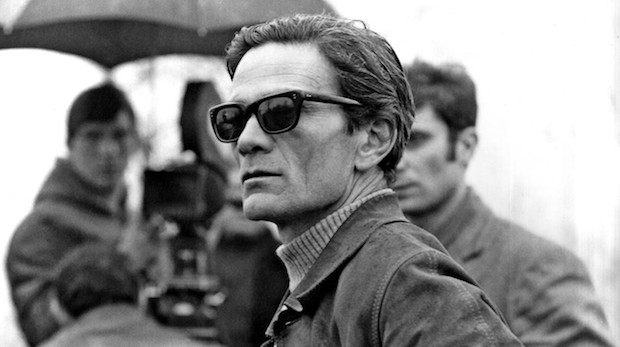

So it is surprising that the first director to do so was a Communist homosexual – Pasolini – murdered on a beach in Ostia in 1975, supposedly by a male prostitute.

Despite his arrest for blasphemy the year before, Pasolini wanted to use only the Biblical text for his “Gospel According to St. Matthew” in 1964.

This September saw the death of the Spanish actor Enrique Irazoqui, who as a young man played the role of Jesus in the Passolini’s film. Although he wasn’t actually an actor by profession, just the son of a Basque psychiatrist and an Italian businesswoman, who had gone to Italy to raise support for the fight against Franco.

After visiting him at his home, Pasolini pursued him until he managed to convince him to play the role of Jesus. After the film, he lived in Cadaqués, where he worked as a teacher in Literature, after one or two other incursions into cinema, as in Dante no es únicamente severo (1967), by Jacinto Esteva and Joaquín Jorda. He ended up being an international chess arbiter.

Well before the 1979 Campus Crusade “Jesus” film, based on the literal words of Luke’s Gospel – although a side-by-side reading shows that there are some things missing – or the Visual Bible project which starts with “The Gospel of John” (2003), Pasolini discovered that in Catholic Italy very few had read the Gospel of Matthew.

He was accused of not having included episodes that tradition has added to the story – such as the veil of Veronica– which Gibson did include in his “The Passion of Christ” (2004).

The genre that has come to be referred to as “Christian film”, has never been known for its great faithfulness to the Scriptures.

To dismiss any nostalgia of the portrayal of Jesus in classical cinema, one only needs to take the Mary Magdalen of Cecil B. DeMille in “The King of Kings” (1927), who is depicted as a rich courtesan, riding a zebra-drawn carriage, trying to rescue her lover Judas from the grasp of the carpenter.

Indeed, this genre has never been very biblical, nor of a very high quality, for that matter. In many ways, these productions show us the worst side of Hollywood in its vulgar exhibitionist sensationalism.

[photo_footer]Nobody expected such a Christ, says Pasolini, because nobody in Italy seemed to have read the Gospel according to Matthew.[/photo_footer]

Even certain evangelical films present us with a blonde and blue-eyed Jesus, straight out of Wisconsin, who seems unlikely to have ever set foot in the Middle East.

In fact, only in 2015, National Geographic became the first to cast an actor who was actually from the region when it produced “Killing Jesus” in Morocco.

You may be getting that I have no great enthusiasm for these films – even when the Easter collection comes around on TV. This may possibly be due to my Protestant upbringing, creating a somewhat iconoclastic attitude in me whenever I see someone trying to play Jesus.

His image was not only taboo among Puritans but it was also prohibited under British censure – from 1912 until after the Second World War when “The King of Kings” finally premiered. He was removed from films like “Golgotha” (1935) and was only kept in Ben-Hur because he couldn’t be seen face on.

I think that there is actually more Christianity in a film like “Ben-Hur” than in any of the traditional films about Jesus. Bathed in a halo of light, we only see his hands in the 1925 version.

In 1959, he has a less ethereal appearance, but he has his back turned and does not say anything.

In Pasolini’s film, however, he doesn’t stop talking, as he walks, or in close-ups – when he gives the Sermon on Mount, only the background changes surrounding him with bolts of lightning.

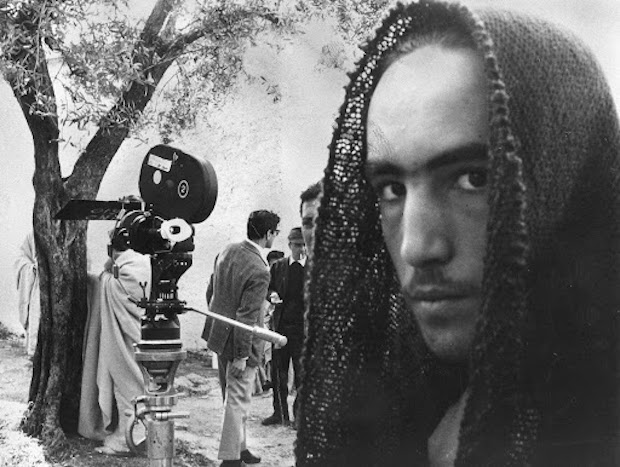

The actors in Christian films always seem to look very serious. They speak in the solemn tone of one who is speaking for posterity. The actors in Pasolini’s film are not professionals, which brings his film close to “cinéma de vérité” style.

The Jesus is played by the Catalan Enrique Irazoqui, who looks Mediterranean – although his father was Basque, his mother was a Sephardic Jew from Padua.

Irazoqui was the nephew of the architect Ricardo Bofill, and he ended up joining the Podemos political party in Spain. It isn’t his voice that we hear in the original version, but that of the actor Enrico María Salerno.

[photo_footer]In September 2020 the Spaniard who played Jesus in the film, Enrique Irazoqui, died.[/photo_footer] Having gone on a reconnaissance trip to Israel and Jordan, returning with five film rolls of documentary material, Pasolini finally decided to film in southern Italy – where Gibson would later do his film – saying that the Biblical locations seemed too modern to him.

It is this same starkness that he sought in his actors. “I didn’t want Christ to have soft features and a gentle gaze”, he explains.

“I wanted a Christ whose face expressed the strength and decisiveness that we find in the faces of the medieval painters”. He wanted “a face that reflected the arid and stony places where he taught”.

In films, Jesus tends to have a gentle image, very peaceful and somewhat asexual. His bland look thus appears ethereal. He seems to float. Human passions are the reprieve of more interesting characters like Judas, Peter or Barabbas.

“No one expects Christ to be like that”, Pasolini explained. “because no one seems to have read the Gospel according to Matthew”.

Contrary to the reactions in England, Pasolini believed that the reactions in Italy demonstrated that “Italians were reading the Gospel for the first time”.

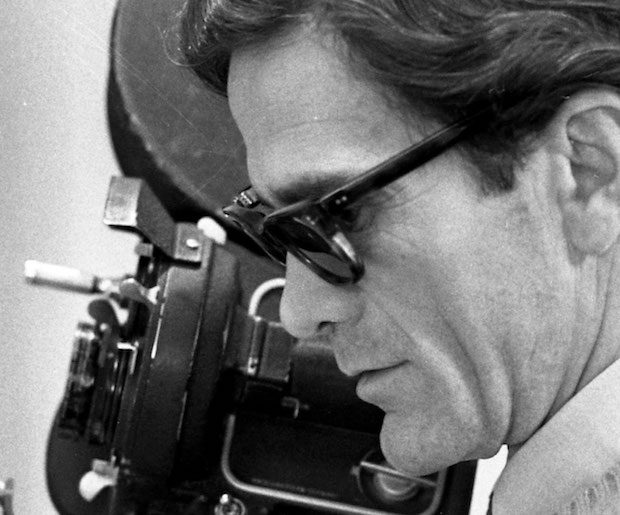

It all started in 1962 when Pasolini was invited, along with other Italian film directors, to a debate series about the relationship between Christianity and Marxism, held in the city of Assis and organized by a Catholic-inspired secular association called Pro Civitate Christiana.

In his hotel room he found a Gospel according to Matthew, which he was very impressed by. “Nothing seems so alien to the modern world”, he said. “than that Christ, loving in his heart, but violent in his reason”. In his excitement, he decided to make a film about the gospel.

He aspired to translate words into images, without leaving anything out of, or adding to, the text. He wanted to maintain the abrupt, elliptical and syncopated style of the evangelist.

He was so excited by reading it that he thought that no other script could reach the “poetic heights” of the original. It is still significant that it required an Atheist Marxist homosexual to recognize the freshness of a direct reading of the Gospel.

[photo_footer]Despite having been arrested the previous year for blasphemy, Pasolini only wanted to use the biblical text to make The Gospel According to Matthew in 1964.

[/photo_footer]

Even though the film is dedicated to Pope John XXIII, Pasolini called himself an atheist: “I do not believe Christ to be the Son of God because I am not a believer”.

However, he also thought that “Christ is divine” because “he elevates humanity to a rigorous ideal”.

As a Marxists, he considered himself to be a rationalist, but he said that “the idea of making this film, I must confess, is the result of a furious irrational feeling”.

Echoing a common sentiment in Catholic countries: “I’m anti-clerical, but I know that there are two thousand years of Christianity in me”.

Pasolini’s father was in the army and his brother died in the Second World War. His passion for poetry came from his mother. As a young man he joined the Communist Party, but he was expelled in 1949, for the “moral indignity” of having sexual relations with some of his students.

He then went to live with his mother in a run-down neighbourhood in Rome, where he found himself working among the poor and the criminal.

That’s when he started to write. His first films show a world of pimps, prostitutes and petty thieves for which he was often accused of indecency.

In portraying the Gospel, he opts for rustic features, faces hardened by the sun and lined with exhaustion. Mary is played by his own mother.

Other acquaintances, such as the brother and nephew of Elsa Morante – the wife of Alberto Moravía – play Joseph and John, respectively: the Hispanist Mario Socrate, plays John the Baptist; the Marxist poet Alfonso Gatto plays Andrew; the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, Philip; the critic and biographer Enzo Siciliano, Simon; and the writer and editor Natalia Ginzburg plays Mary of Bethany.

The soundtrack is a curious combination of the St Matthew Passion by Bach, Mozart’s Adagio and Fugue, and a cantata by Prokofiev, together with African-American spirituals, a Congolese Mass, a Brazilian dance and revolutionary Russian hymns.

The literal text of the Gospel is brought to the screen in a modest production in black and white, which won the Special Jury Prize at the Venice film festival in 1964 (the Golden Lion went to “Red Desert” by Antonioni) and continues to be a matter of fascination today.

Discussions about whether the book or the film is better tends to reveal that there are terrible versions of excellent books, and amazing films of mediocre works of literature.

Nowadays, people generally agree that a film can be faithful to a text, even though it does not stick to it literally.

However, Pasolini edits rather than rewrites the text of Mathew’s gospel. In other words, he omits certain scenes and reorders others, but the dialogues are textual, with no changes or additions – even though he puts the names of the disciples in Jesus’ mouth, rather than in the narrator’s.

The difference with other films, such as the Agape/Campus Crusade “Jesus” film or the “Gospel of John”, is the strength of images in the film, taking the place of a narrator’s voice, which is absent in Pasolini’s film.

That is why it does not include the genealogy at the beginning, nor the dialogues between Joseph and Mary, because they do not appear in the Matthew text. In these scenes, silence acquires a particular weight.

The film does not show the Transfiguration, which appears in almost all films about Jesus – except the “Life and Passion” of 1905.

The clothes of the Jewish leaders look like something out of a Renaissance fresco of the fifteenth century, like those of Piero Della Francesca.

And the Passion is of such a gentleness that it resembles more “The Miracle Maker” (1999) than Gibson’s gory “The Passion of Christ” (2004).

The daily newspaper of the Vatican City, the Osservatore Romano, has said that Pasolini’s film is probably “the best film about Jesus ever made”.

It was awarded a prize by the International Catholic Office for Film Affairs, although Catholic critic Emilio Ranzato said that the film shows “all the elements of the tormented and, for many, contradictory ideology of its Director”, who was recently was played by Willem Dafoe.

Many people ask me which film represents Jesus best. My answer is none of them. Not because the film hasn’t been made yet, but because it never will be. In this case, the Book has no comparison with the film. Since “faith comes by hearing, and hearing by the Word of God” (Romans 10:17). There is no substitute.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o