My Apple Watch lights up to pay, and in my pocket, I feel the buzz of my banking app notification: £2.45 debited for a large latte. Beep, the Oyster card taps seamlessly on the Number 36 bus.

![Big tech companies such as Google, Facebook and Amazon cross personal data of his users to generate huge amounts of benefits. / Photo: [link]R. Sneddon[/link], Unsplash, CC0](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/61376f4decbd1_ross-sneddon-940.jpg) Big tech companies such as Google, Facebook and Amazon cross personal data of his users to generate huge amounts of benefits. / Photo: [link]R. Sneddon[/link], Unsplash, CC0

Big tech companies such as Google, Facebook and Amazon cross personal data of his users to generate huge amounts of benefits. / Photo: [link]R. Sneddon[/link], Unsplash, CC0

We are in the midst of a digitally-enabled industrial revolution. As with previous revolutions, this one is attended by both benefits and perils. In this paper we examine a business model called ‘surveillance capitalism’ that funds the free services of this digital revolution[1]. We describe the model itself; demonstrate the dependence on deception, addiction, and exploitation; and suggest practical responses that individuals and communities can take to face these challenges with hope and assurance.

A soft alarm rouses me from my sleep. The traffic on the road outside is coming alive, rumbles slipping through my double glazing. I’m feeling groggy. Thankfully, the smart speaker is on hand to brighten my morning with my favourite summer playlist – ‘Alexa, play summer soundtrack’. That’s better.

Walking outside, I grab a coffee next door – my Apple Watch lights up to pay, and in my pocket, I feel the buzz of my banking app notification: £2.45 debited for a large latte. Next stop is work. Time to get moving. Beep, the Oyster card taps seamlessly on the Number 36 bus headed up towards my office in London Victoria.

With my iPhone set to ‘do not disturb’ for transit like all other journeys, I enjoy ten minutes of peace. No notifications. No disturbances. Only Spotify streaming my favourite music, as traffic glides by the window of the bus. We pull into the bus stop and off I hop. I scan into work, and the day commences in earnest.

By 9am, the character of our story has only used his smartphone once. Yet by interacting with smart devices four or five times, several hundred data points have been generated. Time stamps, transaction details, geo-tagged locations, and actioned preferences all feature.

[destacate]They have become fabulously wealthy by promoting ostensibly ‘free’ products and convincing the billions who use them to become a product for their own consumption[/destacate]These data points will likely be ‘copied millions of times by some algorithm somewhere designed to send an advertisement,’ and then added to huge databases that enable marketeers to create ‘scenarios’ and ‘outcomes’[2]. Staggeringly, 2.5 quintillion bytes of data[3] are generated every day (that’s 18 zeros). That number will continue to grow. Search engines log around 6.4 billion searches per day.

‘Should I really be worried about this?’, you may say. No single data point is especially significant, but such a substantial aggregation is of great value. This paper explores the scope, scale, and significance of that data capture.

SURVEILLANCE CAPITALISM

Surveillance capitalism: a new economic order built around aggregating human experience as free raw material, for hidden commercial practices of prediction, behavioural manipulation, and sales resulting in unprecedented concentrations of wealth, knowledge, and power in the hands of private companies. [4]

How surveillance capitalism became a dominant force

Surveillance capitalism describes a pursuit for money and power by a handful of privately controlled businesses[5], through the increasingly intimate scrutiny of the lives of billions of people. These businesses have achieved market dominance through aggressive growth, regulatory weakness, and sustained lobbying. They now exert great influence over ideology and imagination across the whole democratic world. They have become fabulously wealthy by promoting ostensibly ‘free’ products and convincing the billions who use them to become a product for their own consumption.

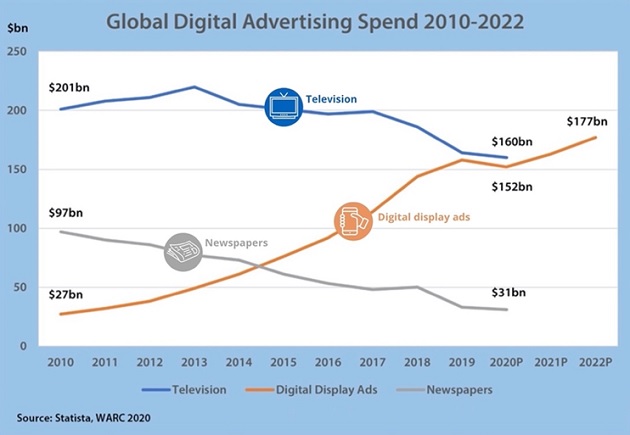

How do surveillance capitalists make money? Much of their income comes from ‘digital advertising’. Between 2001 and 2020, digital advertising grew from 3.1 per cent of total advertising spend, to over 44 per cent[6]. Google, Facebook, and Amazon together receive almost two-thirds of this revenue.

[photo_footer]Global Advertising Spend by Channel. / [7][/photo_footer] In 2001 Google’s annual income was $70 million; by 2020, Google generated $147 billion from advertising[8]. In 2020, 98 per cent of Facebook’s $86 billion income was from advertising. Amazon’s advertising income ($14.1 billion in 2019) is doubling every two years[9].

Moving from prediction to modifying our behaviour

To grow, surveillance capitalists need to extend their influence over what we do. Explicitly, demonstrating links between predicted and actual outcomes (e.g. advertisement leads to sales) increases the value of the services they sell to advertisers. Implicitly, improved prediction accuracy depends on having access to more data and better algorithms. To gain more data, they must increase our ‘engagement’ with their platforms.

Nir Eyal’s book Hooked describes a widely used, algorithm-powered customer engagement model called the ‘hook model’.[10]

It depends on a perpetual cycle of:

Trigger – a system-offered invitation to respond

Action – the user’s response, which results in a...

Variable reward – offered by the system, which provokes further user…

Investment – resulting in another ‘trigger’.

[photo_footer] Hook' Model - Nir Eyal 2014 [/photo_footer] Based on the foundational work of B. F. Skinner and others[11], this model incorporates addictive elements into its core design, mirroring methods used in casinos to keep people playing[12]. Teenagers and young adults are particularly vulnerable to these techniques, but almost anyone will find them hard to ‘beat’. Increasing engagement via the hook model provides both a constant source of behavioural data and a committed audience for advertisements.

These factors make surveillance capitalism much more than ‘improved advertising’ for the twenty-first century. Traditional marketing is hampered by having to choose between targeting accuracy and scale, whereas digital platforms flatten the cost to profile, classify, and target users. Traditional surveys have a relatively fixed cost per question per person. Asking one hundred people one question or one person one hundred questions have similar costs. Asking one hundred people one hundred questions costs significantly more. Surveillance capitalism overcomes this limitation. Digital platforms depend on scale to achieve accuracy, recording behaviours to fuel algorithmically inferred opinions, desires, and expectations. In this model the cost per person is flat and platforms need to maximise the volume of data recorded. By harvesting minute details of actions and responses from billions of people, the platform-owners are able both to classify individuals with precision and predict accurately how individuals within any identified group will respond to a given input. The enormous population of active users, combined with the relatively flat cost per person reached allows even very targeted advertisements to reach large numbers, significantly increasing the ability to influence individuals to achieve a particular outcome.

Origins – grasping the power of data

This began at the turn of the millennium, as the technology-obsessed dot-com boom came to an end. Google discovered that the linked connections between websites provided a good approximation for user interest. They leveraged this massive data set to build a market-disrupting search engine that seemed capable of anticipating what searchers were looking for. They rapidly gained complete market dominance for search but struggled to monetise that disruption.

[destacate]Google realised that more data, and therefore more insight, would come only from expanding into other areas of human life[/destacate]Google considered selling advertising space on search pages, but the founders, Larry Page and Sergey Brin, believed accepting payment for preferential positioning of results would compromise the integrity of their search engine. Ultimately, the need for profits overcame their scruples, perhaps accelerated by Google’s data scientists’ demonstration of how effective the predictive techniques could be in pointing users towards contextually relevant (potentially paid for) content. Surveillance capitalism was born.

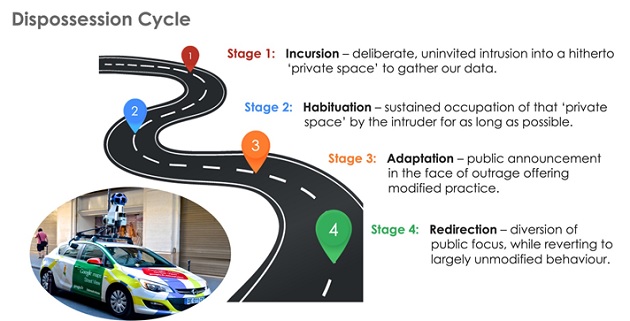

Having taken this step, Google realised that more data, and therefore more insight, would come only from expanding into other areas of human life. They pioneered a systematic approach (labelled the ‘Dispossession Cycle’ by Zuboff) to secure their social ‘right’ to gather data previously considered private.

[photo_footer]Dispossession Cycle (after Zuboff, 2019). [/photo_footer] Surveillance capitalism spreads

In 2008, Facebook had 150 million users, but no user-generated revenue. Sheryl Sandberg was hired from Google as Facebook’s Chief Operating Officer to fix the ‘revenue problem’. Soon afterwards, Facebook asserted ‘ownership’ of all content hosted on their network, regardless of origin, and began selling ‘outcomes’: expected user responses to given stimuli. This led to a now-infamous moment for Facebook, when Cambridge Analytica demonstrated that large volumes of Facebook-originated data could effectively sell ideas, not just products. They are credited with significant ideological movements influencing both the 2016 US presidential election and the Brexit referendum.

[photo_footer] Authors’ representation of key brands associated with some leading technology companies (2020). [/photo_footer] Surveillance capitalists have been eliminating competitors (through lawsuits and acquisitions) and extending their reach through complementary products and services. Amazon used its retail dominance to launch life-integration products like the ‘Echo’ smart speaker and ‘Ring’ home automation product line. This has established mass data collection hubs at the centre of our domestic lives.

[destacate]Amazon has established mass data collection hubs at the centre of our domestic lives[/destacate]Other surveillance companies are doing the same, either using their own products or by integrating third-party devices seamlessly into their own platforms. Apple uniquely seems to be turning its back on these practices, yet they too receive billions of dollars for prioritising Google search on iOS devices[13].

Surveillance capitalists have achieved a huge asymmetry of knowledge and power over consumers and arguably over democratic governments. They are spending heavily to entrench that position: investing in academic research; in medical, social, and political sciences as well as natural sciences and engineering. You don’t have to be a cynic to be concerned that an unregulated monopoly is spending more on political lobbying than any other sector[14].

(Part 2 of this paper will be published next week)

Jonathan Ebsworth has spent his career working with Information Technology. He has recently established a small consulting practice focused on human-centred technology innovation and co-founded www.TechHuman.org, a website aimed at offering insights into how we can live well in a digitally-dominated world.

Samuel Johns writes on identity, immediacy, and technology in the late-modern world, with a particular interest in human personhood. He studied at the University of Oxford before pursuing a Master of Arts at UBC, Vancouver, on the philosopher Charles Taylor's work The Malaise of Modernity.

Michael Dodson is a PhD candidate at the University of Cambridge, studying Computer Science. His research focuses on security and privacy where digital equipment meets the physical world, such as in water and power utilities, medical devices, and automotive applications.

This paper was first published on the website of the Jubilee Centre and re-published with permission.

1. Perhaps first used in Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: the Fight for the Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Profile Books, 2019).

2. Based on words from Jaron Lanier, You Are Not a Gadget (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010).

3. Michael Belfiore, ‘How 10 industries are using big data to win big’, 28 July 28 2016, (accessed 10 May 2021).

4. Based on Shoshana Zuboff, op cit.

5. Private companies that have led the shaping of ideology and imagination in the twenty-first century include Google (Alphabet), Apple, Amazon, Facebook, and Microsoft.

6. ‘GroupM study predicts the internet to take 15% of global ad spend’, Marketing Week, 22 September 2009, (accessed 24 February 2021).

7. Therese Wood, ‘Visualizing the Evolution of Global Advertising Spend (1980–2020)’, 10 November 2020 (accessed 15 March 2021).

8.Joseph Johnson, ‘Google: global annual revenue 2002–2020’, 8 February 2021 (accessed 15 March 2021).

9. Megan Graham, ‘Amazon’s ad business will gain the most share this year, according to analyst survey’, 12 January 2021 (accessed 24 February 2021); Amazon’s advertising revenues are an adjunct to their massive turnover selling products, unlike Google and Facebook whose revenues depend almost entirely on advertising revenues.

10. Nir Eyal, Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products (London, England: Portfolio Penguin, 2014).

11. B. F. Skinner, The Behaviour of Organisms: An Experimental Analysis (Prentice-Hall, 1938) and B. F. Skinner, Science and Human Behaviour (New York: The Free Press, 1966). B. J. Fogg, Persuasive Technology: Using Computers to Change What We Think and Do (Amsterdam: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers, 2011).

12. Natasha Dow Schull, Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).

13. Kate Duffy, ‘Google paid Apple up to $12 billion for a search engine deal that disadvantaged competitors, landmark antitrust suit claims’, Business Insider, 21 October 2020 ([accessed 24 February 2021).

14. Shoshana Zuboff, op cit.: pp.124–125, (Google spending more than any other corporation ($17m in 2014), sustaining that pace through to 2018, and the second highest spender on lobbying in the EU.)

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o