The answer to the question ‘are you religious’ or ‘do you belong to a religion’ depends on what the respondents understand by being ‘religious.’

![Photo: [link]Terren Hurst[/link], Unsplash CC0.](https://cms.evangelicalfocus.com/upload/imagenes/60ccc2c38519f_terrenhurst940.jpg) Photo: [link]Terren Hurst[/link], Unsplash CC0.

Photo: [link]Terren Hurst[/link], Unsplash CC0.

The Nova Index of Secularity presented in this issue of Vista, is based on the European Values Study (EVS) which seeks to understand (among other dimensions) religious belief and practice in Europe.

There are however many factors affecting the outcomes of these and similar surveys such as the European Social Studies (ESS) and the Pew Forum Research Reports. We should be aware of these to understand the nuances of the religious landscape in Europe.

In this article we shall look at some of these factors. Moreover, we shall combine the outcomes of these surveys with demographic trends that have a bearing on religious developments.

The first factor is that surveys use different methods of asking about religious identity which prompt respondents to give different answers. In many surveys, there is a single question, ‘what religion do you belong to?’

Usually, a number of options are added that respondents can choose from, including the indefinite option ‘other’. Other surveys, especially in Europe, take a two-step approach: first a filtering question such as ‘are you religious?’ or ‘do you belong to a religion’ and then, if the response is positive, ‘what religion do you belong to?’ (giving some options to choose from) and further questions about religious beliefs and practice.

Pew researcher Conrad Hackett points out that surveys using this two step measurement strategy tend to find considerably more people reporting no religious affiliation than in surveys with a one-step direct measure of religious identity.

For example, in Austria the 2002 ESS found that 28 percent of respondents claimed to be nonreligious; this was more than double the 12 percent of respondents in this category in the 2001 Austrian census, which included a simple prompt for religious affiliation (Religionsbekenntnis), with a series of response categories including ‘no religious affiliation’ as well as a write-in response box.

In many cases, says Hackett, ‘two-step questions seem to filter out respondents who might otherwise claim a religious affiliation but who do not consider themselves as having a significant level of religious belonging. In some countries where religion is measured with a one-step question, this produces higher estimates of the religiously affiliated share of the country.’ (1)

Based on the single-question approach, the 2018 Pew Research report, Being Christian in Western Europe, says that 71% of the population of western and northern Europe claim Christian identity, and that 22% are regular church attenders (at least once a month).

These percentages are higher than the overall picture emerging from EVS and ESS surveys, that use a multiple question strategy.

A second factor to take in account is that the answer to the question ‘are you religious’ or ‘do you belong to a religion’ depends on what the respondents understand by being ‘religious.’

It means different things to different people and the meaning can vary even among adherents of the same religion.

For some, it means holding religious beliefs. For instance, French people usually say they are ‘a believer’ or ‘religious’, meaning that they believe in God. For others, being religious rather means practicing certain rites and prescriptions of religious institutions.

Having said this, the two-step approach does enable us to go beyond the binary picture of a population divided in a religious and a nonreligious part.

Some people say they are religious, or indicate that they believe in God, pray more or less regularly, and are interested in religious topics, but do not claim to belong to a particular religion.

Social scientists are puzzled by this category, that has been dubbed "believing without belonging" or "behaving without belonging". David Voas has introduced the term ‘fuzzy fidelity’ (2).

A comparison of different surveys shows that this is a considerable part of the population, especially in Western Europe. What exactly do these people believe? Why do they hold to certain religious practices? What is their relation to the Christian (or Muslim) religion?

Inversely, some claim a religious identity while indicating that they are not religious in terms of beliefs and/or practice. They belong to the so-called nominal, cultural or sociological Christians, Muslims or Jews.

In Evangelicalism it is commonplace to distinguish between ‘religion’ and a ‘faith relation with God ‘true faith’. Many are inclined to say that they are ‘not religious’, while definitely identifying as Christians.

A third factor to reckon with is that each survey presents a static picture of the situation at a given moment in a given place, taken from a certain angle, just like a photo. But life, including religious experience and practice, is dynamic, more like a film that consists of a series of pictures that changes over time.

Therefore, it is necessary to compare different surveys. And also, to repeat surveys after a certain time, using the same or at least similar questions, allowing us to see the trends.

That is why this issue of Vista compares the Nova Index of Secularity based on the latest EVS data with the Index of eight years ago. In some countries there a very rapid decline over the last 10 to 20 years while other countries are more stable during the same period.

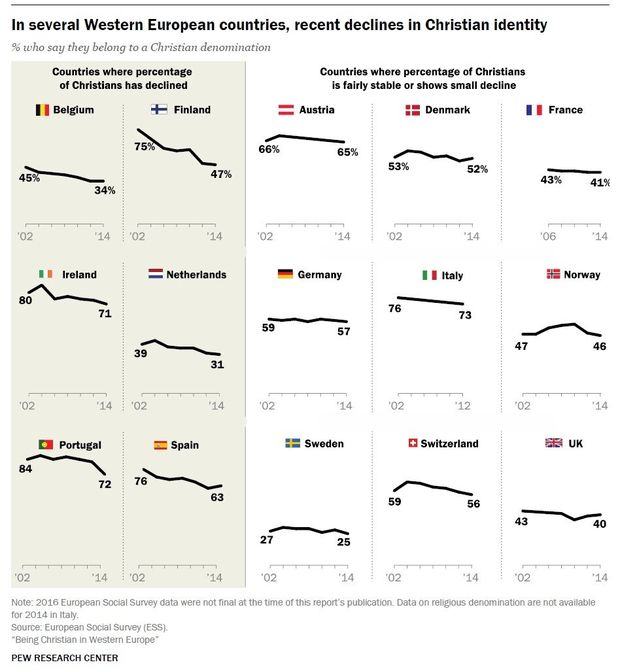

It is interesting to see that France, the UK, Norway and Sweden do not show much increase in secularity, nor in the Pew surveys nor in the EVS. Conversely, there is a considerable rise in secularity the Netherlands, Belgium, Finland, Spain, Switzerland, and Denmark, for example.

Interestingly, some countries show a slight decrease in secularity, which in the Nova Index is noticeable in Germany but also in Hungary and Bulgaria.

The chart below from the 2018 Pew report Being Christian in Western Europe shows the different trajectories in several European countries between 2002 and 2014, with respect to the percentage of the population claiming Christian identity. They vary from a sharp decline to a regain.(3)

Secularisation and the decline of the Christian religion in particular has gone on since for a long time and accelerated since the 1970s. What do these recent trajectories tell us?

Perhaps we can tentatively conclude that the sharp decline in some countries is a matter of catching up with neighbouring countries, and that the decline will slow down and possibly come to a standstill.

Perhaps countries with slow decline, like France and the UK have almost touched the bottom of the decline and are now flattening out. And finally, that decline is not an inevitable process, because in some countries we see an increase in religiosity.

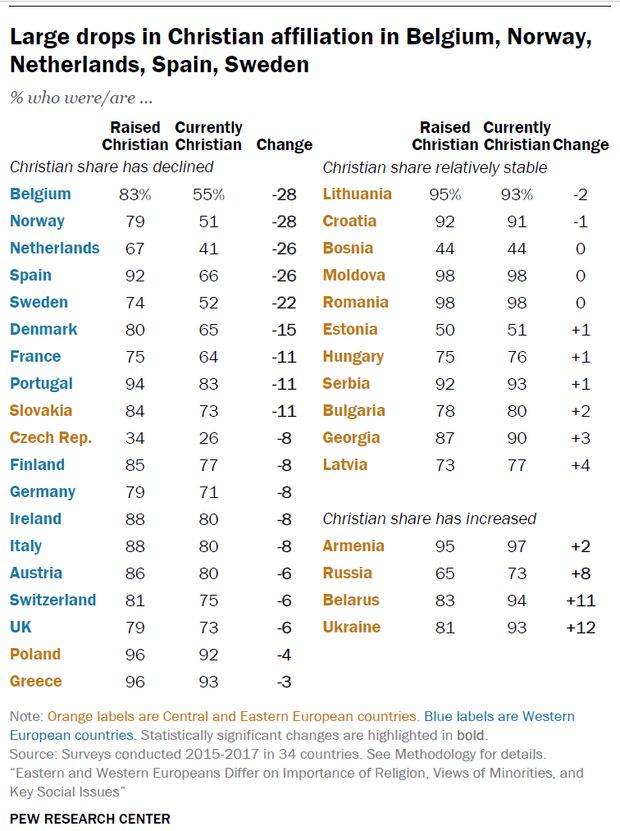

This becomes even more apparent when we look at Europe as a whole. There we observe a striking different between the western and the eastern part. In another recent Pew research report the question was asked how many people who were raised Christian still identify as Christian.

The difference between the two figures equals the decline of Christianity. See below for the statistics, based on surveys conducted in 2015-2017. (4)

In all Western European countries, the number of people who have retained their Christian identity is down, from 6 percent in the UK to 28 percent in Belgium, Norway and the Netherlands. In Central Europe, Christianity is more or less stable, except in Czechia, Slovakia, while in Eastern Europe it shows an increase, even a considerable one, in Russia, Belarus and Ukraine.

You therefore cannot say ‘well, Europe is becoming more and more secularised’, you have to qualify it and highlight that there are different trajectories in Europe with regard to the different countries.

From a pastoral and evangelism point of view, it is not enough to conclude that the nonreligious percentage has increased or decreased so much. We need more refined surveys asking whether people have moved from unbelief to belief, or vice versa, and at what stage in their life.

That brings to light the dynamics of switching (giving up religion, changing religion, converting from being nonreligious to a religion). In public discussions, religious identity is treated as a stable trait.

However, research shows that religious identity (and commitment) fluctuates over the course of life and over time. From the two Pew research reports we have referenced, we learn that a considerable number of Europeans convert from nonreligion to Christianity, but that relatively few indigenous Europeans convert to Islam.

Switching also takes place within a religion, e.g., from being nominal or non-practicing to being a committed and practicing believer – or vice versa.

Many people make a religious switch during their life, but this is not always definite. Some people are religiously liminal, saying one year that they are nonreligious and the following year that they are religious or belong to a certain religion. Others switch from religious to nonreligious.

Why are they no longer affiliated to the religion in which they were raised? This was one of the questions asked in the aforementioned Pew Research Being Christian in Western Europe (5).

Here are median percentages of unaffiliated people who cite one of the following important reasons why they left the religion in which they were raised.

68% Gradually drifting away from religion / the church

58% Disagreeing with their positions on social issues (here we should certainly include questions of sexuality, marriage and gender)

54% No longer believing in the teaching of the religion / the church

53% Unhappy about scandals involving religious institutions and leaders

26% Spiritual needs not being met

21% Religion / the church failing them in time of need

8% Marrying someone outside their religion / church

This brings me to an important point for pastors, youth workers and other church leaders to notice: what are the factors that lead nominal or even practicing Christians to adopting a non-religious lifestyle and worldview?

It is often thought that the major challenge in evangelism is reaching out to non-believers or unchurched people outside the Christian constituency. Statistics of growing numbers of ‘nones’ tend to strengthen this focus.

Far from denying the importance of this focus, I suspect that the church-leavers constitute an even greater challenge. For one, it proves to be quite difficult to arouse an interest in God, Jesus, and the Gospel among people who have already left the church.

In many cases this is too late, they have made up their mind. But what we can and should do is identifying the causes for people to ‘switch out’ and think of the potential leavers in our churches, not only among the young people but in all age categories.

As we study these reasons, and the individual stories of people who have ‘left the fold’, they can become a resource for preaching, teaching and pastoral care.

Do we take into account the factors that have led others to switch out? Are we aware that people within our church constituency might well do the same in the time ahead of us for the same reasons?

Do we realise that some are already in this process, quietly and privately, while we do not see it yet? How can we better notice this? Do we address the issues that cause people to leave? How can we meet the underlying needs, answer the underlying questions, and thereby prevent a process of definite religious distancing to take place in their lives?

By asking these questions our reflection on surveys and statistics can become profitable for pastoral and evangelism practice.

Evert Van de Poll, Professor of Religious Science and Missiology at Evangelical Theological Faculty, Leuven.

This article first appeared in the May 2021 edition of Vista Journal.

1. Conrad Hackett, ‘Seven things to consider when measuring religious identity’. Religion, 2014, , p. 5.

2. Jo Appleton, Reflections on EVS: Interview with Dr David Voas, Vista 38 May 2021

3. Pew Forum, Being Christian in Western Europe (2018), p. 37.

4. Pew Forum, Eastern and Western Europeans Differ on Importance of Religion, Views of Minorities, and Key Social Issues 2018, p. 19. h

5. Pew, Being Christian in Western Europe, p. 41

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o