Biographers of Marc Chagall mention the “gift for happiness,” the “sacred simplicity” which characterized his art, and which was articulated in large part by his ingenious, vibrant use of color.

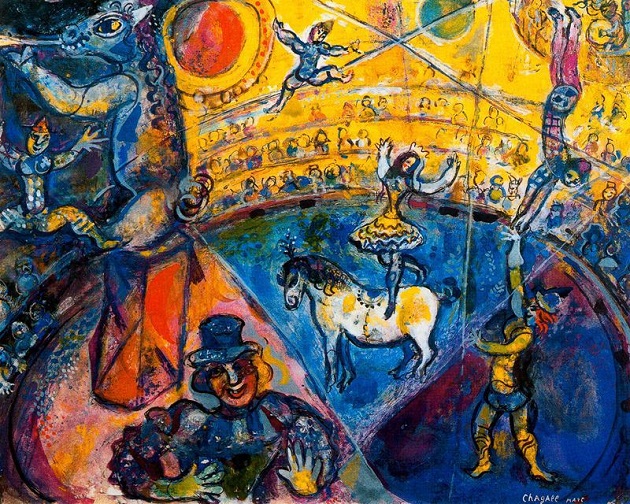

The circus, by Marc Chagall. / Wikimedia (CC)

The circus, by Marc Chagall. / Wikimedia (CC)

Like other painters of his generation, Marc Chagall loved the circus. The delight he experienced seeing clowns and acrobats as a little boy – the unexpected laughs, the beat of the drum, the clumsy smell of the animals, the roar of applause – left an indelible mark in Chagall’s imagination, and influenced his art until his old years. [1]

His painting The Circus, for example, exhibits Chagall’s moving forms and poetic colors to transmit an effervescent atmosphere of youthfulness and innocence, sparkling almost like a young boy’s eyes. “’Circus’ is a magical word,” wrote Chagall once, “the eternal game of dance, in which smiles and tears, the game of legs and arms takes the form of a great art.”

Pregnant with memories of his childhood, Chagall transposed much of the joy and drama of the circus to his paintings. Biographers mention the “gift for happiness,” the “sacred simplicity,” and the “timeless realm of iconic peacefulness” which characterized Chagall’s art, and which was articulated in large part by his ingenious, vibrant use of color. [2] “When Matisse dies,” remarked once Pablo Picasso, “Chagall will be the only painter left who understands what color really is.”[3]

The Prodigal Son, by Marc Chagall. / Wikimedia

The Prodigal Son, by Marc Chagall. / WikimediaChagall’s almost childlike use of color may be what enabled him to craft one of the most moving scenes of homecoming and embrace of all painting. A depiction of the climax of Jesus’ parable about The Prodigal Son – where a son asks for his inheritance and leaves home, and is transformed to see that instead of being rejected, he is welcomed wholeheartedly by the father – Chagall captures the moment of embrace between father and son. It is a gentle encounter, highlighted by the serene eye-contact at the center of the picture. The recovery of intimacy between father and son is stressed also by the empty distance around them – as if to depict an eternal moment of quiet and embrace – but Chagall does not forget to show the reaction of the village too. In an insightful interpretation of Jesus’ parable, Chagall understands that the acceptance by the father is connected to the acceptance of the whole community, who had also been left behind by the prodigal son. But now the crowd cheers his return, there is party and music, and a girl – an old playmate, maybe? – offers him a bouquet of flowers.

But in my view what sets apart Chagall’s portrayal of divine grace even more is his matchless depiction of another consequence of the father’s embrace: the recovery of childhood. Instead of the weariness and cynicism the son had experienced, Chagall’s forms and colors transmit rather an atmosphere similar to that of the circus. He shows that the reconciliation with the father and community meant also a redemption of the son’s past, a retrieval of the innocent youthfulness he had left behind. Now the son could go back to the gardens and squares where he had played as a boy not as a stranger, but as a returned child. There could be laughter, there could be music and dancing, because he who was lost had been found, as Jesus put it; he who had died to the family and the village had come back to life.

“Even today, when I paint a crucifixion or another religious scene,” wrote Chagall, “I experience the same emotions I feel when I paint the people of the circus.” Chagall knew, in other words, that faith is fundamentally a matter of joy. Our restored relationship to the Father, our moment of homecoming is also the moment of our rebirth. It is a celebration, a recovery of innocence, a wholehearted irruption of laughter.

By coming back to the Father we come back home, and are reunited to the youthful past our sin had left behind. There is embrace, there is eye-contact; heaven parties a lost son or daughter’s return, and we rest our heads on the Father’s chest, feeling settled, serene, redeemed.

[1] Goodman, Susan Tumarkin. Marc Chagall: Early Works From Russian Collections, Third Millennium Publ. (2001), 13.

[2] Cogniat, Raymond. Chagall, Crown Publishers, Inc. (1978), 89;; Walther, Ingo F., Metzger, Rainer. Marc Chagall, 1887–1985: Painting as Poetry, Taschen (2000), 38.

[3] Wullschlager, Jackie. Chagall: A Biography Knopf, 2008

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o