Altered Carbon goes a long way to showing us what an eternity without God’s presence would look like.

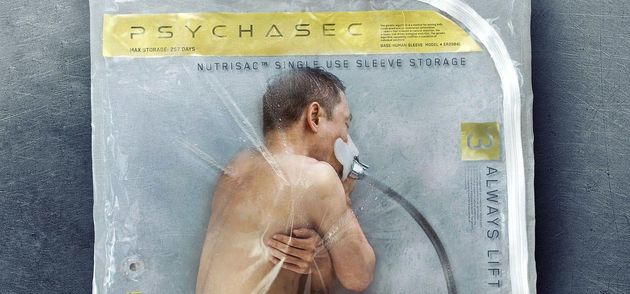

Altered Carbon is set in a future where space-travelling humans have stumbled upon an alien material that allows them to store human consciousness. / Netflix.

Altered Carbon is set in a future where space-travelling humans have stumbled upon an alien material that allows them to store human consciousness. / Netflix.

What if scientists announced tomorrow that you could have eternal life without God –would you be tempted? A continuation of your earthly existence, but without all the heavenly guilt?

Groundbreaking sci-fi series, Altered Carbon, imagines just such a world. Technology has finally trumped death. Yet even as it does so, the church’s take on eternity emerges as more relevant than ever.

Altered Carbon is set in a future where space-travelling humans have stumbled upon an alien material that allows them to store human consciousness.

Now, instead of dying, humans can download their minds to cortical ‘stacks’, which can be inserted into fresh bodies, or ‘sleeves’ when their old bodies die. Virtual immortality is now the privilege of anyone with a big enough bank account.

Standing in opposition to this limitless life, though, is the Catholic Church. A stand-in for all Christian denominations, this version of Catholicism opposes the transfer of consciousness because it teaches that God gave every human one life to live, and immortality is His to bestow.

Christians have won the right to be ‘coded’ so that they can’t be electronically revived, but paradoxically, this also makes them easy to kill without consequences, since the victim cannot return to identify their murderer.

It’s into this physically and spiritually dangerous world, that Altered Carbon’s anti-hero arrives.

Joel Kinnaman (House of Cards, The Killing, Suicide Squad) stars as Takeshi Kovacs, a former elite soldier whose cortical stack has spent 200 years in prison.

He’s revived to solve the murder of one of the wealthiest men in the settled worlds. However, the setting in which Takeshi pursues his case is one fraught with spiritual dilemmas.

The Catholic Church’s opposition to this scientific immortality is presented as the rant of an unreasoning faith. Detective Kristin Ortega, a Hispanic police officer with a religious family, cannot understand why they would take a stand against natural justice:

Kristin: “It’s just really hard to believe in a God that would not allow murder victims to have a voice.”

Uncle: “God works in mysterious ways.”

Kristin: “There’s no mystery. When you’ve seen rape victims, murder victims, people stabbed and shot and strangled, then you know that the only right thing to do is spin them back up, so they can point a finger at the bad guys who attacked them.”

Of course, moral ‘straw men’ like these are regularly used to counter Christianity’s opposition to other disputed freedoms, like abortion and euthanasia. However, the real spiritual tragedy is this world’s failure to understand eternal life.

The majority of Altered Carbon’s characters interpret eternal life as mere longevity – the emphasis is placed on the ‘eternal’ side of the equation.

Considered as such, how could anyone oppose more life, more freedom to experience the universe? Yet Christianity offers a different emphasis.

What the Bible promises those who put their faith in Jesus is eternal life – an endless supply of every good thing, enjoyed in God’s presence: “You make known to me the path of life; in your presence there is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore” (Psalm 16:11) ESV.

What this world and Altered Carbon’s have in common is the belief that it’s possible to enjoy those good things separate of God. But how could that be if He is their source?

In fact, Altered Carbon goes a long way to showing us what an eternity without God’s presence would look like: mere existence without the hope of change to alleviate endless suffering and selfishness. Only, this state is better known as Hell.

Altered Carbon is excellent sci-fi fare for those who like their adventures set centuries in the future. It also includes the same coarse language and nudity that challenge most adult programming.

Its real tragedy, though, is the failure of both the scientists and the theologians to realise that everyone already possesses a guaranteed eternal life, without the need for alien hardware and cortical stacks. How much someone enjoys it, though, depends not on the sleeve they’re wearing, but the person they spend it with.

Mark Hadley, film critic. This article was published with permission of Solas magazine.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o