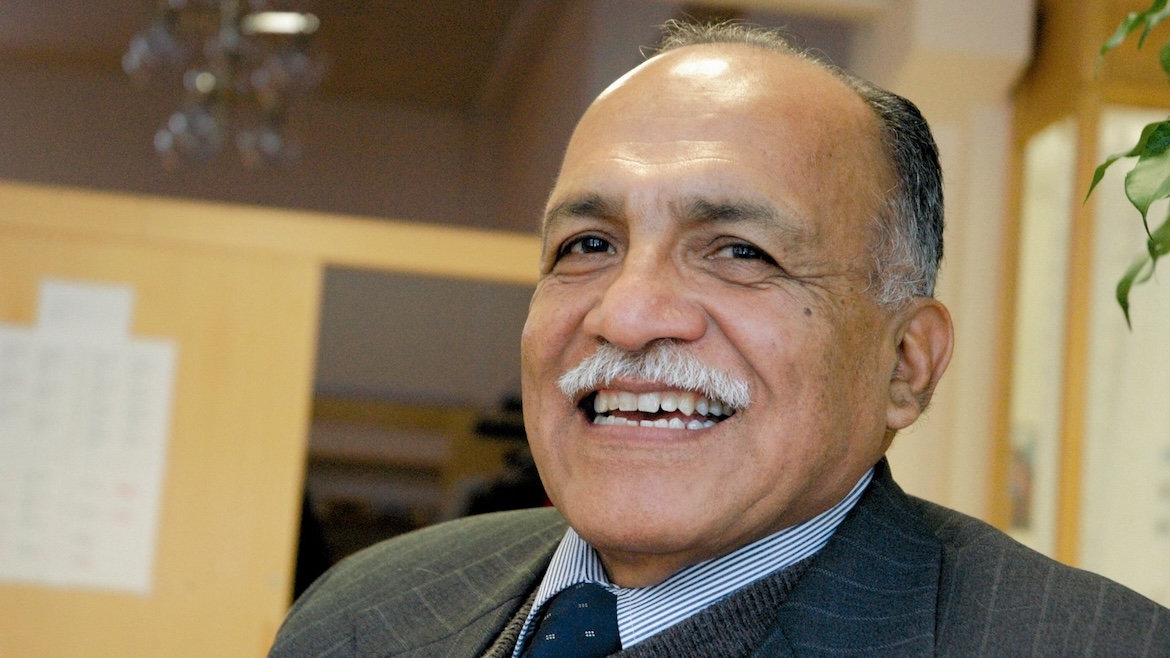

I have learned a lot from Samuel, but what always impressed me about him was his simplicity and humility.

Samuel Escobar passed away on 29 April 2025, at the age of 90.

Samuel Escobar passed away on 29 April 2025, at the age of 90.

Samuel Escobar (1934-2025) is now in the presence of the Lord. He is now enjoying the One he loved and served so much. The smile of the Father will make up for all his sufferings and sacrifices. He is already safe in the arms of the One who gives us the peace that the world cannot give.

When I produced a series of twenty radio programmes - now podcasts - about his life and work, my greatest hope was that he would be able to listen to them in person. Thanks to his daughter Lilly, he listened to them every Sunday as he left the residence.

I wanted to record this long series of interviews when he was still very lucid, but without the responsibilities that made him reluctant to say openly what he felt and thought about anything. His body was increasingly frail, but his mind was agile and alert.

One of the privileges of teaching at the Protestant Faculty of Theology - formerly the Seminary of the Evangelical Baptist Union of Spain - in Alcobendas (Madrid), was to be with one of the people I have most admired since I was a teenager. I have known his name since I was a child.

I used to read the magazines and books published by Escobar since the 1960s in Argentina, when my father started the work of the Christian Literature Centre (CLC) in Spain with a clandestine bookshop in an office he opened on the centre of Madrid when Samuel came to the capital city of Spain to do his doctorate in 1966.

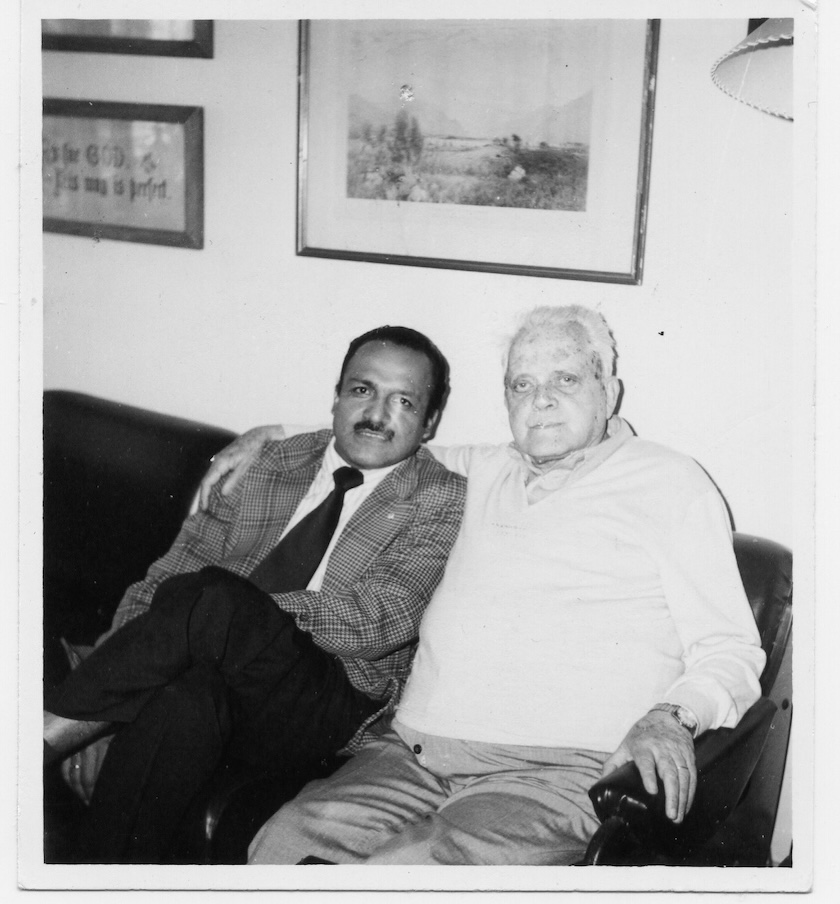

[photo_footer] Samuel Escobar with his teacher, Alejandro Clifford, in 1981. [/photo_footer] A professor of English literature in the Assemblies of the Brethren at the University of Córdoba (Argentina), Alejandro Clifford, had asked him to continue writing for a “Christian magazine for people who think”, called Certeza (Certainty), after he had started another one in Villa María, called Pensamiento Cristiano (Christian Thought), where Samuel Escobar, René Padilla and so many others also wrote.

Samuel learned journalism from Clifford who, along with his studies of literature and pedagogy in Lima (Peru), gave him that agile and refined style of writing, so far removed from the rambling texts that continue to weigh down most evangelical literature in Spanish.

Anyone who has read one of his texts will be amazed at the fresh and pleasant style with which he writes, which is unusual for authors of such theological depth. His language has always been simple and clear, especially when he preaches.

When I arrived at the Biblical University Groups (GBU, a member of IFES international), I noticed the deep impression he had left with materials such as ‘Dialogue between Christ and Marx’ or ‘Who is Christ today?

When my friend Marité Pérez-Prida came from Córdoba to Madrid in 1983 to continue her law studies, she told me about Samuel, his daughter Lilly and Clifford's granddaughters at the Argentinian Biblical University Association (ABUA), which made me even more eager to meet him.

Escobar had gone with his son at that time to Calvin University in Grand Rapids (Michigan, USA), but in 1984 he began to teach at the Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, and that is when I began to write to him.

It was a great honour for me to be able to publish some of his articles in a magazine he co-edited with my father, 'Reformation Papers', including a monograph on the revision of ‘the black legend’ in 1992, which attributed the rise of evangelical churches in Latin America to a CIA strategy.

Little could I have imagined that one day I would be teaching with him in Madrid, listening to his biblical expositions, participating in the cloister, or simply having a coffee with him. It is one of the greatest joys I have had at the Faculty. I never got tired of listening to him.

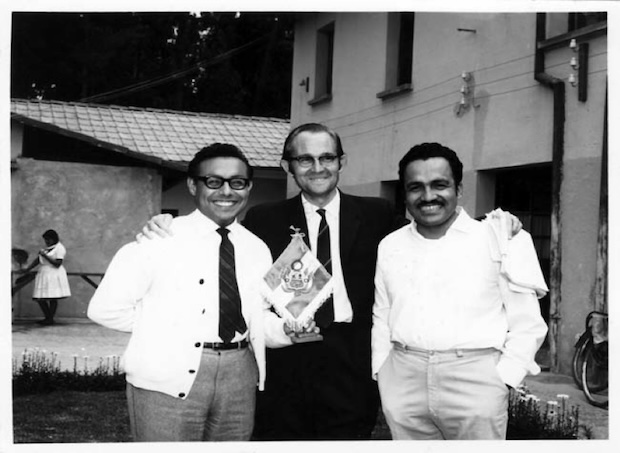

[photo_footer]Pedro Arana and Samuel Escobar, together with Pedro Savage, founders of the Latin American Theological Fraternity with René Padilla. [/photo_footer] I asked him about his life, which made me more and more curious. It was fascinating to follow the course of his biography from the day that the midwife who attended his mother, when he was born in his home in Arequipa (Peru) in 1934, was the same English missionary who brought the now deceased Nobel Prize winner, Mario Vargas-Llosa, into the world.

When I started taking him to the radio studio to record interviews, I was surprised to hear him talk about his parents' separation. His father was a police officer, who had converted to the evangelical faith with his mother a couple of years earlier.

Samuel grew up with her. He went to a missionary school and was the only Protestant student among the five hundred who attended the secondary school in Arequipa, known as “the Rome of Peru”.

Samuel remembers very well the books he used to read to his mother, who could not read, while she was sewing. He liked to listen to the Proverbs and the lives of missionaries that he was given at school and Sunday school.

He was a passionate reader since his adolescence. In Lima he discovered the work of Unamuno through Juan A. Mackay, the missionary of the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland who founded the Saint Andrew's school in Lima and was with Don Miguel in Salamanca, later confronting the ‘witch-hunt’ in the Princeton seminary.

Samuel delved into Peruvian literature when he studied literature in the 1950s at the University of San Marcos, but graduated with a degree in pedagogy.

He had grown up in an independent church “where there was no historical awareness or pastoral ministry” he recalled. In Lima he was confronted with the university world, where Marxism was a powerful ideology. Students were beginning to become aware of the extreme poverty and oppression in Latin America.

The military dictatorships, guided by liberal economists, were based on corrupt administrations that revealed a brutal contrast between the wastefulness of a privileged minority and the misery of the majority.

[photo_footer] Together with Stott, Samuel became part of the small team that organised the Lausanne conference in 1974. [/photo_footer] Baptised by a Southern Baptist missionary in the United States, Samuel experienced the tension between “the Marxist ideological package that never quite convinced him”, and a preaching, or literature, that did not reflect the biblical vision that responded to the challenge of the Marxist vision.

However, his involvement with a Baptist church helped him greatly, where he learned to communicate with ordinary people, putting into practice the guidance he received from the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES), for which he ended up working.

Escobar was a Peruvian delegate to the 1953 Baptist World Youth Congress in Rio de Janeiro, and to the first meeting of evangelical students, held in Cochabamba (Bolivia) in 1958.

He went to that conference from Lima with the Presbyterian chemist and theologian Pedro Arana, his other great collaborator, and René Padilla. René was an Ecuadorian, living in Argentina, who came from the Assemblies of Brethren and had done his doctorate with F. F. Bruce at the University of Manchester (England).

All three ended up playing a key role, not only in the student work, but also in the founding of the Latin American Theological Fraternity in Cochabamba in 1970.

The statement and contributions of Escobar, Padilla and Arana to ‘The Contemporary Debate on the Bible’ were published by José Grau in Barcelona - along with those of the Nazarene Ismael Amaya and the Anglican Andrés Kirk, who was my teacher at John Stott's institute in London.

Those who were described - both then and now - as “liberation theologians” should read the papers published in that book, to see how far they were from the critical presuppositions of Scripture that characterised the Commission on Church and Society in Latin America (ISAL) - sponsored and supported by the World Council of Churches.

In 1984 Samuel wrote: “I have not moved one iota from the firm convictions expressed there regarding revelation, inspiration and the authority of Scripture”.

In 1966 the founders of the prestigious magazine Christianity Today, Carl Henry and Billy Graham, organised a conference on evangelism in Berlin. Samuel was invited by Clifford to present a short paper on “evangelism and totalitarianism”.

There he found an evangelical landscape that knew of no other threat to the gospel than communism. In his paper he courageously argued that the danger in Latin America was also military dictatorships linked with Roman Catholicism.

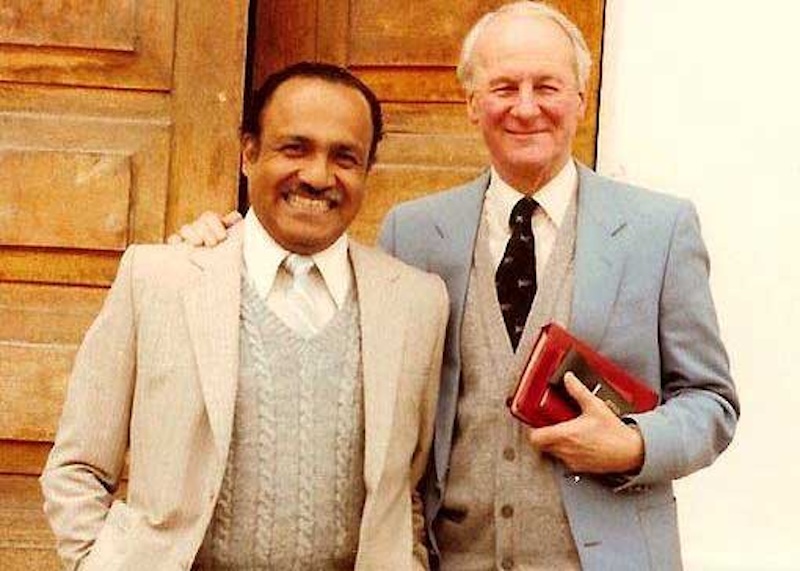

Samuel appreciated the integrity of the evangelist Paul Little in his leadership of the university work in Canada. Through him and John Stott, he became part of the small team that organised the Lausanne conference in 1974.

There he “witnessed more than once, with sadness, the unclean political and ecclesiastical dealings of some of the leaders of the large evangelical institutions”.

[photo_footer] Samuel with his wife Lilly back in Lima in 2002. [/photo_footer] The tensions he experienced there brought him closer to Stott, who was about to leave the organisation in a heated confrontation with Billy Graham, who decided one night not to follow the instructions of his many advisors and the next morning handed over responsibility for the Lausanne Covenant to Stott.

Escobar's and Padilla's affinity with Stott led to them holding two of the main plenary sessions at Lausanne (Switzerland) in 1974, where José Grau (theologian from Barcelona) also had a brief participation with a paper on the kingdom.

Rene Padilla's paper was particularly controversial as it strongly criticised the pragmatic principle of “homogeneous units of church growth” from the book of Acts, the popular idea that the church grows more among those who have something in commo. It asked not whether it works, but whether it is biblical.

Escobar had already begun to develop his work in English, since his papers at those congresses were not only in English, but he also led the Anglo-Saxon student work in Canada.

When he attended a seminar in Chicago on the social concerns of evangelicals, “some Latin American friends” began to say that he had 'adopted a more conservative theology'.

Some begin to distinguish Escobar from other members of the Fraternity, such as Padilla, considering that “there has been a deterioration of fundamental convictions over time”.

To both criticisms, Samuel responded that the Fraternity's declaration in Cochabamba in 1970 continued to express his own convictions about the Word of God.

He stood by Arana's criticism of ISAL as “a theology that subjects the Word to Marxist ideology”.

The opposition of the more conservative sectors, linked to the interests of North American organisations, led to a campaign against the Latin American Congresses of Evangelisation (CLADE), promoted by the Fraternity, as well as the foundation of a new movement, called CONELA, Confraternidad Evangélica Latina (Latin Evangelical Confraternity).

If you want to know Escobar's position on those issues, you have to read the book published by Casa Bautista de Publicaciones in 1987, La fe evangélica y las teologías de la liberación (The Evangelical Faith and the Theologies of Liberation). For me, it is the definitive work on this subject.

Spain is the country where he has spent the most years of his life, having arrived in 2000. He settled in Valencia with his daughter and his increasingly ill wife.

At first he still travelled abroad a lot, publishing more and more in English. Some of his last books were later published in Spanish, but most people do not know that, behind the simplicity of his biblical expositions, there is an extraordinary level of scholarship.

Many appreciate him for his humility, but few know the depth of his thought, which he develops mainly in English.

Some of it can be appreciated by reading the translation of The New Global Mission (2003), published by Certeza, How to understand mission, as well as In search of Christ in Latin America, published in Buenos Aires by Kairós in 2012-, but much of it is difficult to find in Spanish.

That time in Spain was not easy for him. Illness has accompanied him in recent years. His wife Lilly suffered from Alzhaimer's since 2004, being cared for by Samuel and his daughter, while he teaches at the Faculty of Alcobendas.

During this time of trial, he has seen God's power grow stronger in her weakness (2 Corinthians 12:9). Despite his fragility, he was animated and full of ideas, always interested in the present.

He used to tell me what he had read on Saturday in the cultural magazine of Spanish newspaper El País. And he was one of the people who encouraged me most to write about film.

I have learnt a lot from Samuel, but what has always impressed me most about him is his simplicity.

One of the things that has surprised me most in life is that the greatest men of God I have met are also the most humble. They are not pretentious and pedantic people who like to know themselves. Quite the opposite.

What always impressed you about Escobar was his grace and generosity. In fact, I have only seen that in John Stott, Tim Keller or José Grau in Spain.When I studied at Stott's Institute for Contemporary Christianity in London in the 1980s, he often invited me up to his penthouse for dinner. To get upstairs you had to go through a narrow room where he had a small bed surrounded by books all along the corridor. It didn't take me long to realise that I couldn't take any of them off the shelf to look at, because he would immediately say: 'Take it away!' I had only ever seen such generosity in Samuel Escobar.

I was not surprised to hear Stott say one day that he learned to live more selflessly when he met Samuel.

I have never been so dissatisfied with material things, but every time I saw Samuel, I understood that the kingdom of heaven belongs to the 'poor in spirit' (Matthew 5:3). There is nothing more contradictory than a proud Christian.

In fact, humility and meekness are the only virtues the Lord said we should learn from him (Matthew 11:29). It was what characterised Moses (Numbers 12:3), but when he lost it, he was excluded from the Promised Land.

There is too much tolerance for pride in the Christian world. We are full of people who rub our spiritual successes or moral superiority in our faces. It is all publicity for our great achievements and values. We are more like the Pharisee in Jesus' parable than the tax collector who cried out for God's mercy (Luke 18:10-14).

That is why there is so little grace in the world around us. We are so self-satisfied that we think we are superior to everyone else. That's why we don't stop lecturing them.

In a society that admires the strongest, Jesus tells us that it is the meek who will inherit the earth (Matthew 5:5). They will not conquer it by their own strength, but it will be given to them as an inheritance. It is a gift we receive by grace through faith, not as the fruit of our own efforts (Ephesians 2:8-9).

Martin Lloyd-Jones said that true humility comes from really knowing who we are. We need Samuel's honesty to stop defending ourselves.

Those who know their own misery have no trouble listening to the criticism of others because they know that if they knew what we were really like, they would say worse things about us!

I once heard Stott say to someone who had praised him highly that if he knew what he was really like, he would spit in his face. It is the wonder of grace that makes us marvel at God's mercy that enables us to show grace and mercy to others.

Generosity comes from knowing that “all things are ours, and we are Christ's, and Christ is God's" (1 Corinthians 3:21-23). He is not a fool who gives up what he cannot keep to gain what he cannot lose, wrote Jim Elliot, the missionary who died for the Huaorani in Ecuador.

Escobar's life is an example of grace and generosity that we should imitate in order to be like the Master, but it is also a gift from God for which we should thank the Father and ask him to make us more like him.

José de Segovia, theologian and journalist in Madrid, Spain.

[analysis]

[title]Join us to make EF sustainable[/title]

[photo][/photo]

[text]At Evangelical Focus, we have a sustainability challenge ahead. We invite you to join those across Europe and beyond who are committed with our mission. Together, we will ensure the continuity of Evangelical Focus and our Spanish partner Protestante Digital in 2025.

Learn all about our #TogetherInThisMission initiative here (English).

[/text][/analysis]

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o