It is no coincidence that John Le Carré, the master of spy fiction, was himself a spy. He knew what he was talking about. The mistake of conspiracy theories is to believe in perfect plots.

His work as a spy taught Le Carré that nothing is what it seems.

His work as a spy taught Le Carré that nothing is what it seems.

The author John Le Carré died at the end of 2020. I loved his spy stories as a teenager. I suppose that it is at that age that the distance between who we appear to be and the universe within us grows in giant leaps.

According to the Spanish author Javier Marías, spies embody the duality of the human being. They live in a dark and complex world where nothing is at it appears to be. Le Carré’s stories make us wonder who we really are, where our loyalties lie and whether anyone is really innocent.

Graham Greene and John Le Carre wrote some of the best spy stories that I have read. It is no coincidence that they were both spies, so they knew what they were talking about.

The mistake of conspiracy theories is to believe in a perfect plot, because nothing is perfect in this world, and we all make mistakes. Power is not exempt of foolishness: the ware and tare of pressure, the carelessness that comes with time and simple human stupidity mean that we all slip up.

Le Carré was an expert in camouflage. He would rarely give interviews and not even in his memoirs did he talk about his work as a spy. Even the origin of his pseudonym – his real name was David Cornwell – remains a mystery.

It is no surprise then to discover that his father was a fraudster who did time in prison in various countries. The spy trade doesn’t come easy.

In his memoirs, Le Carré did recognize that he had made mistakes, but, as his biographer Adam Sisma discovered, his declarations were full of contradictions. After having written seven-hundred pages about him, Sisman realized that the problem wasn’t that he lied about himself, but that he was an expert at getting rid of any trace of his past, muddying the difference between lived and imagined experience.

This is why biographies can never be taken as the ultimate truth about a person. Our memory is a fickle thing – it erases certain memories and rustles up others.

The author of The Spy Who Came in from the Cold worked as a British agent in Bonn during the Cold War. He never revealed any of his sources, but said that “rule one” was that “nothing, absolutely nothing, is what it seems”.

This constant doubt was born out of constant self-criticism, which allowed him to distance himself from the fame that he acquired. Vanity brought on by success leads to a lack of awareness, but there is a certain wisdom in the mature and disillusioned characters that figure in the novels of Le Carré – as well as in Graham Greene’s – which we do not find in the James Bond-type spy.

I have learned a lot from Le Carré’s books, both about the evil caused by the ingenuity of those who never mistrust anyone, and about the subtle attraction of conspiracy theories.

We prefer to believe that our lives are conditioned by a plot laid out by the forces of evil, rather than by the chaos that is produced by human stupidity and selfishness.

Conspiratorial thinking likes to explains things as the machinations of the devil, but forgets the problem that the Bible calls sin. We are sinners before we become devils.

Espionage cannot be understood without taking account of human curiosity: “We all want to know what’s really going on”, says James Grady, author of the The Six Days of the Condor (1974), the book that inspired the splendid film by Sidney Pollack and Robert Redford (The Three Days of the Condor, 1975).

“Starts when we’re kids. What’s inside this box? Behind that closed door? By the time we’re teenagers, we’re pretty sure there’s a “real world” somewhere beyond our high school halls, a time and place where things make sense, where who’s in charge is something we can find out – and that knowing who and what runs “the real world” will help us live our dreams”.

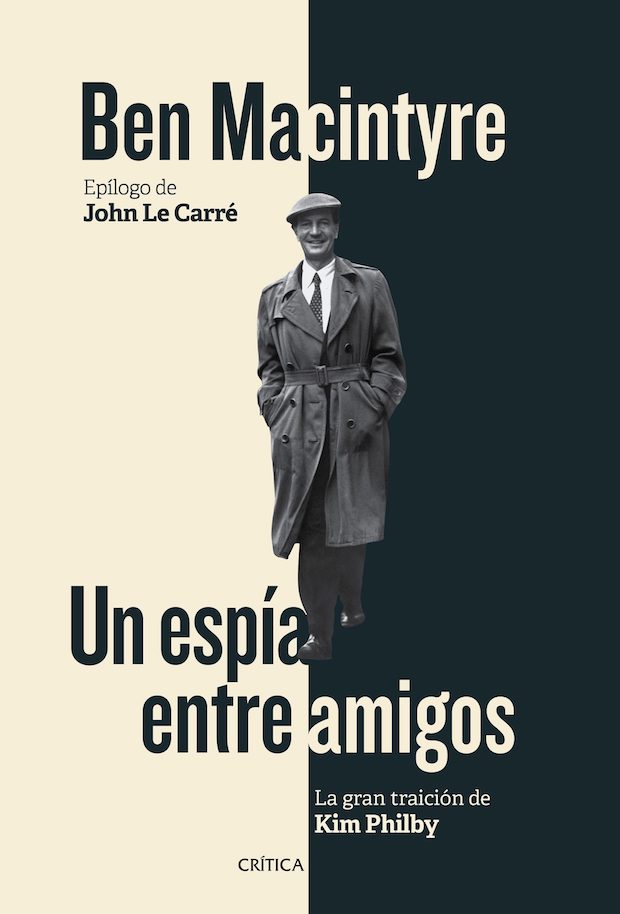

The twentieth century probably knew no better spy than Kim Philby. He was the embodiment of the character in J.K. Chesterton’s The Man who was Thursday: A Nightmare – the leader of a subversive organization, so secret that it was led by the chief of police in charge of tracking it down.

For many years Philby was in charge of running the British Secret Service’s investigations and intelligence on the Soviet Union, while also being the KGB’s most important double agent in the West. He was both the hunter and the prey; the hero and the traitor.

The book by Ben Macintyre, A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal, is an impressive story of deception. His best friend and MI6 colleague Nicholas Elliot had, like him, received an elitists British education at Eton College and Cambridge University.

They shared a passion for cricket and they both belonged to the same exclusive clubs in which people talk with the right accent, wear the same tweed jackets and are capable of drinking themselves blind without ever losing their stiff upper lip.

Their shared drinking habits made it impossible for Elliot to suspect that every word that he uttered was sent back to Moscow by Philby.

And as if this were not enough, Philby became a close friend of the head of the CIA, James Jesus Angleton. In this way, Philby was able to undermine the operation of Anglo-American intelligence for some twenty years.

As suspicions closed in on him, he told ever greater lies to hold up his façade. He was never caught because his two best friends never abandoned him.

They didn’t realize that since 1934 he had been what is commonly known as a “mole”, a double agent serving the interests of the Soviet Union, while working at the top of the British intelligence service.

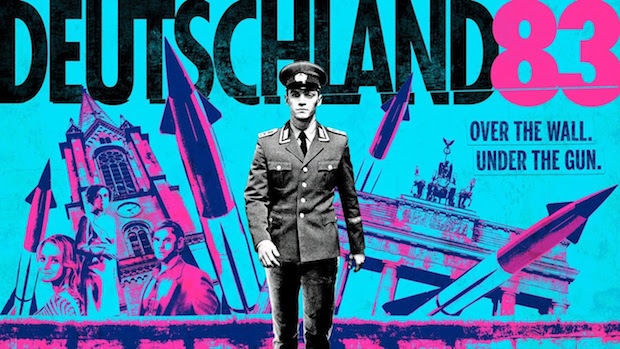

Deutschland 83 is the first German series to be aired with subtitles in the United States, before it appeared on German television. Produced by the Wingers, a German couple, it tells the story of a young border patrol guard of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany), whose aunt, a STASI official, recruits him by force to go undercover as an aide to a high-ranking NATO officer.

His mission is to find out about the Allies’ plans to deploy nuclear missiles. This all takes place during the Reagan era and the music is a selection of “techno-pop” with and Nena’s earworm 99 Luftballons (translated into English as 99 Red Balloons) at the top of the list.

The Americans is another TV series that has gradually won people over. It was created by a former CIA agent, Joe Weisberg, who is fascinated by the real story of soviet spies who went undercover in the United States, taking on fake jobs and identities, and going so far as having a family like the one that appears in the series.

The main characters go through countless disguises and subterfuges, but the story becomes really interesting when they reveal what they really do to their daughter, who has become a member of a Protestant church and has decided to get baptized, despite her parents’ staunch atheism.

In this regard the plot is similar to that of the The Good Wife, which depicts an atheist lawyer whose daughter also becomes an evangelical Christian.

The creator of the Homeland series, Howard Gordon, says that spy stories take place “in that gray space between good and bad”. That is why we are able to sympathize with the characters, even when they are guilty of disloyalty, torture and betrayal. They exemplify the fact that “There is no one righteous, not even one” (Romans 3:10).

If we mistake faith with credulity, it is because we do not know ourselves. We do not realize our capacity for self-deceit (Jeremiah 17:9). The Christian world appears to obey the unwritten rule of pretence.

We talk as if we lived a life of obedience to God, when that is not the case. We say that this and that is God’s will when in reality it is our own.

We act like we believe, when in fact we doubt. We hide our weaknesses behind an image of perfection, perpetuating the illusion of something fake. We pretend that we have a perfect marriage and a happy family, when they are as dysfunctional as any others.

When people ask each other how they are, the answer is never “Not good, thanks”, because no one wants to hear that, or has the time or interest for it. We relate to each other on the basis of a pretend identity.

The reality that we cover up is that we are a disaster. Our spirituality is chaotic; we all have problems. No one is perfect. We have many secrets and when we stop pretending, the bubble that we live in bursts.

We have to face the reality of our failure. This is our way into the Kingdom of God. Jesus says that when we confess our hunger, thirst, grief, wants and poverty we are “blessed” (Matthew 5:3–12), in other words, accepted by God.

It takes that level of despair to realize that we don’t have anything in this life, apart from what God is for us in Jesus Christ. Hopeless people often do not fit in well at church. They are strange and unbalanced, but when they taste God, they cannot turn their backs on Him.

We distance ourselves from God because we don’t want to appear before Him as we are. We are waiting to become clean and complete before seeking Him. We believe that until we have cleaned up our mess, Jesus won’t want to have anything to do with us.

We do not realise that God loves people like us who are dirty and incomplete. These “damaged goods” are the “materials” that God chooses to work with, even before we have chosen the right way to live.

It is when we recognize our indignity and unattractiveness, that we discover the value that we hold for Him. It is not until we have recognized our mess, that Jesus can do anything with us.

Christ is looking for those who are lost, ahead of those who have found themselves; the losers, ahead of the winners; those who have been broken, ahead of those who are whole; those in a state of disarray, ahead of those who have it all figured out; the disabled, ahead of those who believe themselves capable.

In His grace, He is chasing us in order to finish the good work that He once begun (Philippians 1:6). Meanwhile, let us fix our eyes on Jesus (Hebrews 12:2). Once He has brought His work to completion, there will be no more double agents. We will be who we really are, in Jesus Christ.

Las opiniones vertidas por nuestros colaboradores se realizan a nivel personal, pudiendo coincidir o no con la postura de la dirección de Protestante Digital.

Si quieres comentar o